On this page

- Abbreviations and special terms used in the report

- Executive summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Assessment objective, scope and methodology

- 3.0 Legal basis for the assessment

- 4.0 Background

- 5.0 Findings

- 6.0 Food safety program requirements

- 7.0 Implementation of food safety controls and government oversight at the farms, packers and exporters

- 8.0 Laboratory capacity

- 9.0 Closing meeting

- 10.0 Conclusion and recommendations

- Annex A: Summary of the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Agriculture's action plans/ comments to the CFIA recommendations from the assessment report of Costa Rica's Food Safety Control System for Fresh Fruit

- Annex B: Roles and responsibilities of the key departments involved in food safety in Costa Rica

Abbreviations and special terms used in the report

- AyA

- Instituto Costarricense de Aqueductos y Alcantarillados (National Water Authority)

- CA

- Competent Authority

- CATR

- Central American Technical Regulation

- CCSS

- Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social (Costa Rican Social Security Fund)

- CFIA

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- ECA

- Costa Rican Accreditation Entity

- EM

- Environmental Manager

- EU

- European Union

- FF

- Fresh Fruit

- GAPs

- Good Agricultural Practices

- GHPs

- Good Hygiene Practices

- GMPs

- Good Manufacturing Practices

- INA

- National Training Institute

- INCIENSA

- Instituto Costarricense de Investigacion y Ensenanza en Nutricion y Salud (The Costa Rican Institute for Research and Education in Nutrition and Health)

- INFOSAN

- International Food Safety Authorities Network

- ISO

- International Organization for Standardization

- LNA

- Laboratorio nacional des aguas (National water laboratory)

- LRE

- Laboratorio de Análisis de Residuos de Agroquímicos (Laboratory for chemical residue analysis)

- MAG

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganaderia (Ministry of Agriculture)

- MEIC

- Ministerio de Economica, Industria y Comercio de Costa Rica (Ministry of Economy, Industry and Trade)

- MOH

- Ministerio de Salud (Ministry of Health)

- NCs

- Non-compliances

- NFSS

- National Food Safety System

- PPE

- Personal Protective Equipment

- PROCOMER

- Promotora del Comercio Exterior de Costa Rica (Promoter of Foreign Trade of Costa Rica)

- SEPAN

- Secretaría de la Política Nacional De Alimentación y Nutrición (Secretariat of the Food and Nutrition Policy), MOH

- SENASA

- Servicio Nacional de Salud Animal (National Animal Health Service

- SFE

- Servicio Fitosanitario Del Estado (State Phytosanitary Service, MAG)

- USA

- United States of America

Executive summary

This report summarizes observations and recommendations made during the 2018 on-site assessment of Costa Rica's government oversight of food safety controls for fresh fruit by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA).

The main objective of the assessment was to increase CFIA's understanding of Costa Rica's food safety system as it relates to fresh fruit and, to verify its implementation.

The assessment was conducted from February 26 to March 9, 2018 at various sites in 4 provinces in Costa Rica which included: meetings with the key competent authorities responsible for the food safety of fresh fruit (the Ministry of Health; MOH and the Ministry of Agriculture; MAG), 3 farms, 3 packing facilities and 3 laboratories.

The assessment determined that Costa Rica has established general food safety requirements for the production, packaging, and exportation of fresh fruit including Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) and Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs). These requirements provide an environment for the production of fresh fruit under sanitary conditions. The current programs are implemented by well-trained, competent people who are dedicated to their work.

This report provides several recommendations which highlight opportunities to enhance the effectiveness of current requirements.

The observations and recommendations contained in this report are based on information provided to the assessment team through the Canadian Assessment Standards tool, personal interviews, and on-site observation. They represent the collective understanding of the members of the assessment team.

1.0 Introduction

An assessment of Costa Rica's food safety control system for fresh fruit (FF) was conducted in Costa Rica from February 26 to March 9, 2018, by a team from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency's (CFIA) Food Import and Export Division. The ten-day mission included:

- interviews with Costa Rica's competent authorities (CAs) involved in the implementation and oversight of the food safety controls for FF (the MOH and the MAG)

- visits to facilities involved in the primary production, packaging, storage and export of various FF (melons, papayas, pineapples) – including fields and packing facilities

- visits to the government laboratories involved in the testing of fresh produce and water including: the microbiology and chemistry laboratories of the Costa Rican Institute for Research and Education in Nutrition and Health (Instituto Costarricense de Investigacion y Ensenanza en Nutricion y Salud; INCIENSA), the MAG Laboratory for the Analysis of Agrochemical Residues (Laboratorio de Análisis de Residuos de Agroquimicos; LRE), and the National Water Laboratory (Laboratorio nacional des aguas; LNA)

An opening meeting was held with the CAs on February 26, 2018. During this meeting, the CFIA explained the objectives and the technical aspects of the assessment. The CAs provided an overview of their roles and responsibilities.

From February 27 to March 7, 2018, the team visited farms and packing facilities that produce/pack FF for export. Representatives of the CAs accompanied the assessment team throughout the visit.

A closing meeting was held on March 9, 2018, to summarize the observations of the team, including opportunities to further strengthen the national food safety system.

2.0 Assessment objective, scope and methodology

The key elements of the assessment included:

- Authorities

- Current food legislative authorities, including regulations, standards, codes of practice, and arrangements

- Authority to carry out microbiological risk assessments, monitoring and surveillance activities

- Authority to respond to non-compliances (NCs) where risk has been identified such as recalls, other control and enforcement activities

- Government organization and resources

- The roles and responsibilities of the various government departments and authorities involved in the food safety system

- The resources, responsibilities, functions, and coordination between the parties involved in the food safety system

- Resources and competencies of the CAs involved in the delivery of the food safety system

- Analytical support facilities and programs for example, laboratories, monitoring programs, etc.

- Inspection, enforcement and surveillance activities

- Role of the CAs in inspection, surveillance, and enforcement

2.1 Methodology

The assessment was comprised of three phases.

- Phase I – A desk review of information provided to CFIA through Costa Rica's response to the Canadian Assessment Standards (CAS) tool.

- Phase II - An on-site visit to observe the implementation of the food safety requirements by the government bodies.

- Phase III - Drafting of the assessment report to summarize the assessment team's understanding of the food safety requirements by the government bodies and to highlight opportunities to further strengthen the system.

2.2 Assessment scope summary

The visit focused on primary producers and packers of FF. The number and variety of units visited provided a representative sample of commodities, diversity in size, complexity, and geographical location to allow the team to draw an unbiased conclusion about the implementation of the system as a whole. In addition, the assessment team met with the CAs and laboratories as outlined in Table 1.

| Site | Number | Locations |

|---|---|---|

| Competent Authority | 2 | San Jose |

| Farms | 3 | Various locations |

| Packers/Exporters Table Note 1 | 3 | Various locations |

| Laboratories | 3 | San Jose |

Table Notes

- Table Note 1

-

Note: Farms and packing facilities were co-located

3.0 Legal basis for the assessment

This assessment was conducted in agreement with the Costa Rican CAs and under the CFIA's Import Requirements for Fresh Fruit and Vegetables outlined in Section 3.1 (1) (b) of the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Regulations and Section 4 of the Food and Drugs Act. In particular:

- Section 3.1 (1) (b) of the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Regulations:

- "Subject to subsection (2), no person shall market in import, export or interprovincial trade as food unless it is not contaminated."

- Section 4.(1) of the Food and Drugs Act:

-

"No person shall sell an article of food that

a. has in or on it any poisonous or harmful substance;

b. is unfit for human consumption;

c. consists in whole or in part of any filthy, putrid, disgusting, rotten, decomposed or diseased animal or vegetable substance;

d. is adulterated; or

e. was manufactured, prepared, preserved, packaged or stored under unsanitary conditions."

-

4.0 Background

Costa Rica's FF industry consists of operations that range in size, complexity, and capacity. Nearly half (48.472%) of the farms in Costa Rica are less than 5 acres in size while fewer than 5% of farms are larger than 100 acres. Farms may be independent operations that service only the local area or, large multi-national companies which trade internationally. All locations observed had reliable basic services (electricity, running water etc.). Some of the larger operations offer on-site health and social services, for their employees. Several operations also run well-developed environmental programs which demonstrate their strong commitment to the environment and, community-oriented programs which are designed to improve the health and economic status of their communities.

Costa Rica's main FF export crops are pineapple and bananas which are produced year round. Other FF crops are seasonal. Costa Rica's main exporting market for FF is the United States of America (USA) and the European Union (EU).

FF is typically imported into Canada from Costa Rica either directly or via the United States. The key FF products Canada imports from Costa Rica include pineapples, bananas, and melons Footnote 2. Fifty-five (55) % of Costa Rica's papaya production is exported directly to Canada.

5.0 Findings

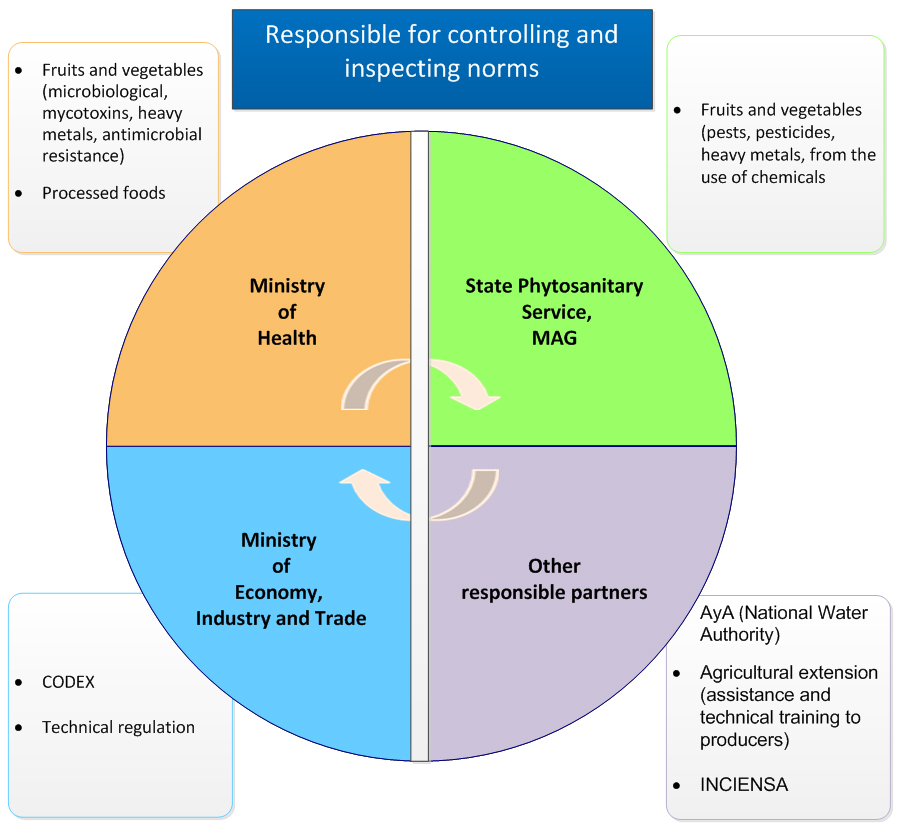

In Costa Rica, the responsibility for food safety with respect to FF is covered by multiple pieces of legislation, and responsibilities are shared across multiple government departments, including: the MOH, and MAG (see Annex B).

In general, chemical food safety is the responsibility of the MAG while general food safety is the responsibility of the MOH.

Other government departments with supporting roles include:

- Instituto Costarricense de Aqueductos y Alcantarillados (AyA), responsible for water quality and safety

- Ministerio de Economica Industria y Comercio (MEIC), responsible for Codex work and, the development of technical requirements

- Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social (CCSS), responsible for public health

- Promotora del Comercio Exterior de Costa Rica (PROCOMER), responsible for promoting foreign trade

5.1 Regulatory foundation

The framework for FF food safety in Costa Rica is established by several laws, decrees and other instruments under the responsibility of both MOH and MAG, as outlined in Table 2.

| Instrument | Name | Ministry |

|---|---|---|

| Law 5395 | The General Law of Health | MOH |

| Law 5412 | The Organic Law of the Ministry of Health | MOH |

| Law 7664 | The Phytosanitary Protection Law | MAG |

| Decree 35485 | Microbiological Criteria for Food Safety | MOH |

| Decree 33724 | GMPs for Processed Foods | MOH |

| Decree 37057 | Good Hygiene Practices (GHPs) for Non-Processed and Semi-processed Foods | MOH |

Additional decrees focus on potable water, health surveillance, sanitary registry, inspections, outbreak management, alerts, sampling and analysis, and the maintenance of health records. Each regulatory tool is supported by instruments to promote compliance: protocols, guides etc.

Costa Rica is a member of the Central American Technical Regulation (CATR) Committee which establishes technical requirements (standards) at the Central American level. Any regulations made at the Central American level must be complied with by each of the signatory countries. In fact, they supersede any existing national law(s).

For example, the CATR for Microbiological Criteria for Food Safety provides sampling protocols and acceptability criteria for various foods for the purpose of registration and surveillance, and, the CATR for GHPs for Non-Processed Food or Semi-Processed Food establishes general provisions and hygiene practices for unprocessed foodsFootnote 3.

5.2 Development of the national food safety system

In aims of coordinating food safety activities at the national level, Decree 30083/17/01/2002 established a Ministerial Council and the Inter-sectoral Commission on Food Safety. The Ministerial Council supports the coordination of all activities of this initiative. The Inter-sectoral Commission identifies the roles and responsibilities of each Ministry involved in food safety in aims of developing a single national food safety system.

The commission is comprised of various ministries in 3 key sectors: health, agriculture and economy. These are further supported by strong participation from all sectors including agriculture, education, business and civil society (national association of consumers).

The Inter-sectoral Commission, coordinated by the Secretaría de la Política Nacional De Alimentación y Nutrición (SEPAN) of the MOH developed Decree 35960/3/05/2010 that established the National Food Safety Policy. Although the supporting structure to enable this decree has not been fully developed or implemented, the team observed strong commitment to this initiative from senior representatives of both MOH and MAG.

The CAs explained that they are in the process of developing a National Food Safety System (NFSS) in which the government departments will work closely together to provide a more integrated and coordinated approach to food safety in the future.

Costa Rica plans to work on a system to establish alerts and use the International Food Safety Authorities Network (INFOSAN) as a focal point. INFOSAN assists Member States in managing food safety risks, ensuring rapid sharing of information during food safety emergencies to stop the spread of contaminated food from one country to another.

5.3 Government roles and responsibilities

This section describes the main roles of the key ministries involved in FF food safety under the current structure.

5.3.1 Ministry of Health

The organizational structure of the MOH is presented in Annex 2.

5.3.1.1 National structure

The Direction of Regulation of Products of Sanitary Interest is responsible for the development of regulations, protocols and procedures related to food. They are also responsible for annual food control plans and, for ensuring compliance with the CATR for Microbiological Criteria for Food Safety. This group has the authority to issue recalls and other corrective measures in the case of a NC. Laboratory Analysis related to the annual food control plans are carried out at INCIENSA.

SEPAN is the secretariat for national food policy. It also coordinates other activities related to food and nutrition; for example, food safety issues. SEPAN also leads the coordination of the NFSS.

The Direction of Customer Care is in charge of both imports and exports. It issues:

- technical notices

- health-related import requirements

- export certifications when required by an importing country

The Health Surveillance Authority is responsible for issuing food safety alerts.

5.3.1.2 Regional structure

Under the MOH, there are 9 regional offices and 84 governing (local) areas which range in complexity based on population and, the nature of the local industry.

The MOH employs environmental managers (EMs) who conduct activities according to their diverse mandate and responsibilities (from food safety to fire and earthquake safety) including:

- inspections to verify implementation of MOH regulations (not just food safety)

- issuing operating sanitary permits to establishments as a pre-requisite to operate

- training companies on the implementation of the MOH regulations

The number of EMs per region varies from 3 to 8 people depending on the needs of their area. There are approximately 500 EMs.

EMs conduct GMP/GHP verifications at FF establishments against the requirements in the CATR for GHPs for Unprocessed Food. EMs follow an established written procedure which requires written evidence to be left at the establishment inspected. The CFIA team noticed inconsistencies in compliance of this requirement.

5.3.1.3 Training

Standardized training is delivered at national and regional levels for consistency. Costa Rica's National Training Institute (INA) provides food safety training to government employees, industry and, local citizens. Government employees are trained through Train the Trainer sessions who can then also provide free training to industry.

EMs are required to have a 4 year degree (BSc or equivalent) before they can be hired. The CFIA team observed that most are biologists, microbiologists, or environmental specialists.

EMs receive 1 year of comprehensive training from INA at the beginning of their career before they can conduct activities independently. The training covers all of their areas of responsibility (food, fire, earthquake safety etc.). Successful candidates are considered to be Professionals in Regulation of the Civil Service. Refresher training is provided as required.

The scope of roles and responsibilities of EMs is currently being reviewed to determine whether more specific responsibilities (instead of broad ones) or alternate methods of delivery (for example, 3rd party delivery) could make their work more efficient.

The assessment team was informed that the Inter-sectoral Commission is developing standardized training for several ministries including MOH, Servicio Nacional de Salud Animal (SENASA), MEIC etc. The goal is to increase knowledge and understanding of each other's roles and responsibilities across the food continuum in aims of strengthening the system as a whole. In the future, participants will receive a food safety inspection certificate.

5.3.1.4 Monitoring and surveillance

The MOH focuses on microbiological, mycotoxin, heavy metals, allergens and labelling issues. Samples are taken according to annual control (sampling) plans which are developed in coordination with INCIENSA. Priorities are established based on the requirements in the Microbiological Criteria for Food Safety CATR, previous history of compliance, the risk classification of the food etc. Regional offices may have enhanced sampling plans depending on the area's specific needs and history, for example, type of production, and previous issues.

The MOH has the authority to take samples from both processing facilities and from the marketplace. Sampling for the annual control plan is typically conducted at markets in San Jose unless additional sample units are required to make up a sample size in which case samples may be taken in the regions. Sampling may also be conducted as part of an investigation.

Samples are analyzed by the INCIENSA National Reference Center laboratory. The MOH is informed of any positive results and may issue a sanitary order which can trigger corrective actions, re-sampling, seizing product on a precautionary basis while compliance is being confirmed, market withdrawal, recall, and/or suspension of products and/or risk communication. All sanitary sanctions available are documented in an MOH decree. In 2017, 3,014 analyses were conducted, resulting in 29 sanitary orders.

The team was not able to confirm whether the MOH conducts risk assessments to determine appropriate actions or, whether every positive finding is treated the same way.

5.3.1.5 Outbreak investigation and response

Outbreak investigation and response is guided by the Protocol for Surveillance of Food and Water-borne Diseases for Outbreak detection and Intervention. The team did not have the opportunity to observe or discuss in detail Costa Rica's outbreak response protocols and procedures due to time constraints.

5.3.2 Ministry of Agriculture

The Servicio Fitosanitario Del Estado of the MAG (the SFE) is responsible for the oversight of chemical food safety of FF in Costa Rica. The organizational structure of MAG-SFE is presented in Annex 3.

5.3.2.1 National structure

The Law of Phytosanitary Protection (7664) provides the legal authority to regulate pesticides, including the use and management of chemical, biological, or related substances for agricultural use to protect human health and the environment. To achieve this, SFE's activities focus on:

- registration of pesticides

- control of the quality of agricultural inputs (pesticides and other inputs)

- assessing the quality of agrochemicals to ensure free from contamination

- auditing of chemical storage areas

- control of pesticides in food

- promoting the use of GAPs to prevent inappropriate use/storage/disposal of agrochemicals

- testing FF (at farms, markets, entry and exit points), runoff water, and agricultural soil for pesticide residues

This work is conducted by 3 employees at headquarters and 60 employees across 8 regions.

The law also gives SFE the authority to:

- sample, seize or prevent the importation of non-compliant food

- to retain or destroy FF that contain pesticides residue levels above the maximum limitFootnote 4

SFE's activities are enabled by a series of decrees. Decrees are also used to prohibit the use of specific products. For example, carbofurans, bromacil, endosulfin, malathion.

5.3.2.2 Regional structure

Regional SFE staff are responsible for verifying GAPs and chemical residues.

They take samples for pesticide residues according to an annual sampling plan which considers geographical location, crops and inputs typically used in their production, diet, origin of product (imported or for domestic versus export), prior history etc. Soil, water, and sediment are usually sampled in follow up to positive results. A total of 5,500 samples were taken in 2017, of which 50 were non-compliant. Samples are collected on Mondays and are sent to SFE's LRE for analysis (6,000 – 7,000 analyses per year). This service is delivered at no cost to farmers, but importers are responsible for the cost of analysis of imported products.

Regional inspectors rotate to promote impartiality when conducting inspections. In the case of NCs, regional staff take samples and observe the operation for 6 months to ensure compliance.

Regional facility visits are integrated and include chemical residue sampling and phytosanitary requirements.

Employees from one regional office can be sent to another region to assist in inspection activities. Inspectors conduct inspections of plant packaging facilities.

Each region develops an annual operational plan which includes sampling and training.

Regional SFE staff is also responsible for verification of and training on GAPs, including follow up activities. They train local producers in areas of highest risk which are identified through the results of the annual sampling plan. SFE staff also provide advisory services in the development and implementation of GAPs by providing model systems, and crop-specific manuals. Nine thousand (9,000) producers were trained in a period of 1.5 years.

SFE staff also routinely conducts GMP inspections at packing facilities. They document the results in an official government document (referred to as a 'log book') which is kept at the facility. A carbon copy of the findings is taken by the inspector.

5.3.2.3 Training

Both SFE headquarters and regional officers are trained on GAPs and GMPs. Since the EU and US are Costa Rica's main markets for FF, much of the regional officer training focuses on EU and US food safety and import requirements.

Regional officers are also trained to take samples. Refresher courses are provided as needed. For example, a refresher on sampling was delivered to all 120 government personnel in 2017.

Industry is trained on GAPs/GMPs by SFE and by trading partners (EU, US, Canada). The training provides knowledge and tools to food producing companies and agricultural producers who export.

Regional SFE staff provides quarterly training to farmers to address trends in NC. This training includes GAPs, sampling, integrated pest management, maximum residue limits, personal protection equipment (PPE) etc. SFE can provide financial support to farmers for training. SFE also trains people who sell pesticides who in turn can educate farmers on the appropriate use/handling of their products.

In addition, the SFE prepares manuals, as well as radio and television campaigns which highlight GAPs (integrated pest management, equipment and calibrations, preparation, storage and disposal, use of personal protective equipment) and food safety issues identified in specific crops such as, strawberries, mangoes, pineapple and cilantro. The television/radio campaigns target both industry and, the general population to encourage consumers to demand food quality and safety.

SFE communicates closely with the MOH in cases of water pollution and aflatoxins, but there is no national process for communicating between regional offices of SFE and MOH.

5.4 National Water Authority

Following a history of poor water quality, AyA, was delegated responsibility for management and stewardship of municipal water and sanitation services for the country, and, given the mission to improve the quality of the water from aqueduct sources. Water from rural or community wells and, water within food establishments is under the jurisdiction of the MOH while water for irrigation is regulated by the MAG.

AyA's work is supported by a series of laws and decrees which gave them the authority to create a national laboratory for potable water (LNA) and, a water purification plant at the centre of the union. The Drinking Water Law (2015) provides chemical and microbiological analyses and criteria which are based on criteria established by the World Health Organization.

Today, Costa Rica boasts that 93.9% of water from aqueducts is safe and potable.

5.5 Promoter of Foreign Trade of Costa Rica

PROCOMER is the institution in charge of promoting the export of Costa Rican goods and services throughout the world. Created in 1996 through the Law of the Republic number 7638, they also facilitate the exportation procedures, generate exportation chains, register exportation statistics of goods, and perform market studies. Before companies can export their products they must register as an exporter with PROCOMER. A single window centralizes and facilitates import and export procedures including registration, technical requirements, and guidance for certificates of origin. A certificate is issued as evidence of registration.

6.0 Food safety program requirements

The CFIA team observed that under the regulations, there are no requirements for farms, packing and processing facilities to have a food safety program in place. However, the MOH and SFE regulations do require operations to comply with GAPs (farms) and GMPs/GHPs (packing facilities).

The MOH is responsible for approving all food processing facilities (including packers) by issuing a sanitary operating permit. This is based on verification of compliance with GHPs/GMPs.

Operators apply for a sanitary operating permit by submitting an application form, a declaration/affidavit signed by the company, emergency plan and corporate ID. The permit is valid for 1 year at which time the operator must resubmit their application if they choose to reapply. The MOH usually takes 1 month to review the application. The MOH is required to conduct an inspection prior to issuing a permit for high risk foods such as FF. Once the MOH issues the permit, an EM from the local office conducts an inspection to verify the information submitted in their application. In the case of NCs, the EM requires a corrective action within a timeframe appropriate to the NC. Once the corrective actions are addressed by the facility, the EM reviews them for completeness. During the on-site inspection, the EM inspects/reviews food safety and non-food safety components of the facility including the exterior of the facility, equipment/utensils, hygiene controls, pest controls, sanitation controls, GMPs etc. The inspection is based on a points system with the highest points representing a good system. Facilities are classified as A or B based on the risk of their products and facility.

Inspections are generally conducted according to the level of risk which is defined in the CATR. Inspections may occur to confirm GMPs/GHPs for the purpose of granting/verifying the conditions of an operating permit, or, to follow up on complaints. The MOH may conduct an unannounced inspection at any time.

The CFIA team observed that the SFE does not issue any formal permit/certificate which allows farms or packing facilities to operate. However, during the growing/packing season, each facility is frequently inspected by the SFE's Regional inspectors. Regional inspectors review the policies and procedures, GAPs (in the fields), and GHPs/GMPs (in packing facilities). They may also sample FF for chemical residue testing. If a positive result is detected, the company is required to investigate the source of the contamination. If a follow up sample is positive, the MOH is contacted.

7.0 Implementation of food safety controls and government oversight at the farms, packers and exporters

The assessment team focused on verifying the implementation of the following GAP and GHP/GMP elements:

- general requirements and infrastructure

- hygiene

- training and skills development

- traceability and recall

- validation procedures and sampling

- records

- standard operating procedures

- flow diagrams

- other records to support the implementation of their food safety programs

The assessment team visited three farm and packing facilities. The products for these facilities included melons, papayas and pineapples.

The CFIA team observed that the facilities were committed to the implementation of food safety practices and, that they have 3rd party food safety certifications, such as Global GAP. Although these were a common requirement for trade, they are not a government requirement.

The CFIA team noted the following about the three facilities.

- Infrastructure was generally appropriate for the activities conducted and included systems in place to control exit and entry of workers, visitors, and wildlife

- Operators had sanitation and hygiene controls in place in the fields and packing facilities

- The majority of employees are long-term employees or return on a seasonal basis. Employment is solicited through the local communities

- Employee entry procedures (hand washing, no jewellery, wounds etc.) were clearly posted in strategic areas (entry point of the farm, packing facility etc.). Employees were required to wear PPE during production

- Employees were trained on general topics every year such as hygiene, internal procedures, good handling practices of agro-chemicals, use of PPE etc. and on additional topics like specific procedures as required

- Employee hygiene was monitored and documented routinely, for example, at start up, after breaks etc. Procedures are in place to remove employees if they don't meet the general health/hygiene requirements and, to retrain staff if appropriate

- Appropriate washroom facilities were present with sufficient supplies

- Operators had implemented documented sanitation and pest control programs

- Operators implemented detailed traceability systems which allowed them to trace a product back to the farm and lot of origin, and in many cases, to the picker, packing line, implements used etc. Mock recalls are conducted at least once a year to test the effectiveness of their plans. Records demonstrated that although the procedure is implemented, there are some areas for improvement to ensure that operators are able to respond to real life situations

- Pesticides and agro-chemicals were stored in secure areas accessible only by designated trained staff. Controls were in place for the disposal of empty agro-chemical containers. Agro-chemicals were handled only by trained staff

- Operators conducted regular internal audits of their food safety program as required by their 3rd party food safety certification

- Food safety controls were in place for the sanitation of transport trucks

- Operators implemented annual surveillance plans and maintained detailed records for the analysis of water, workers' hands, surfaces, product, soil etc. Plans varied between operators but generally included analysis of basic microbiological indicators (fecal coliforms, Salmonella spp. and Escherichia coli and chemical contaminants (heavy metals, pesticides etc.). Samples were taken by the facility's trained personnel, external contractors, or an accredited laboratory contracted to conduct the analysis

All the packing facilities visited had a sanitary permit, but the period of validity varied from 1 to 5 years. Facility staff indicated that the MOH may visit their facility for other reasons such as inspecting Zika virus controls or, if they receive a complaint about the facility. However, no evidence of such visits were observed at the facilities (verbal only).

Several operations also have on-site medical staff. If they determine that an employee should not work, the employee is referred to the local municipal clinic where treatment is provided. Employees cannot return to work until they have been cleared to do so by the local clinic and/or the resident medical personnel.

The packing facilities visited were major exporters to countries including Canada, USA, Japan and Europe. The facilities were aware of the export requirements of their products including registration with PROCOMER and the single window system. The facilities had an exporting code as required by MAG and were aware of the requirements for obtaining a certificate for export.

8.0 Laboratory capacity

8.1 The Costa Rican Institute for Research and Education in Nutrition and Health

Law No. 8270 (2002) makes INCIENSA responsible for laboratory-based epidemiological surveillance, research in public health themes and the teaching and education processes derived from its work. Originally founded as a hospital for sick children, the focus of this institution was on nutrition. It now serves as a national laboratory for public health, serving several government organizations including the MOH, and in the case of outbreak investigations, the MAG, and AyA.

INCIENSA has 7 different specialized units (reference centres). For example:

- The National Reference Centre for Microbiological Food Safety which analyzes both food and water using both traditional and molecular microbiology methods (whole genome sequencing, antimicrobial resistance) for a variety of foodborne pathogens including: Salmonella spp., Listeria monocytogenes, pathogenic and indicator Esherichia coli, Staphyloccocus aureus, Clostridium perfringens, Vibrio spp., Cronobacter, and Shigella spp. Future analyses will include viruses, parasites and anaerobes. Additionally, they conduct molecular typing for genetic markers, and molecular subtyping of foodborne diseases as well as for anti-microbial resistance. They are expanding their scope to include whole genome sequencing

- The National Reference Center for Bromatology which analyzes for the presence of chemical residues, aflatoxins, heavy metals, mycotoxins, allergens and verifies the nutritional composition and labels of foods for export as per the MOH requirements

INCIENSA analyzes samples taken by the MOH EMs under their annual sampling plan and, during outbreak investigations to determine compliance to the CATRs. Results of analysis are communicated to the MOH by email.

INCIENSA does not currently receive samples from the public. Industry samples must be analyzed by private laboratories. Although private laboratories do not generally report positive analysis results to INCIENSA, they can request INCIENSA to conduct subtyping of notifiable organisms such as Salmonella spp. The information will then follow through the National Surveillance System.

INCIENSA's laboratories are accredited to International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 17025, ISO 9001-2015 and ISO 17043. In June 2017, INCIENSA was accredited by the Costa Rican Accreditation Entity (ECA) for several additional methodologies for food. INCIENSA is currently building a new laboratory which will allow for the expansion of their scope of testing methodologies.

The facility is appropriate for use, and has implemented processes to maintain chain of custody, limit access to authorized personnel etc. Staff are well-trained and aware of their internal policies and procedures to deliver reliable results.

INCIENSA is part of several laboratory networks, including the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the Inter-American Network for Food Analysis Laboratories, The Global Foodborne Infections Network, and PulseNet Latin America and Caribbean. INCIENSA participates in external proficiency tests to confirm the ongoing exemplary quality of their work. They are also audited internally and externally by ECA every 12 months (6 months apart). ECA's last audit was observed to have been conducted on 19 June, 2017.

8.2 Laboratory for chemical residue analysis

The SFE's LRE is responsible for performing pesticide residue analysis on fresh fruit, vegetables and grains. They test both imported and domestic products. The laboratory is accredited by ECA to the International Standard INTE-ISO/IEC 17025:2005. Additionally, they work according to the Good Laboratory Practices guidelines and follow the guidance of SANTE/11945/2015 Analytical quality control and validation procedures for pesticide residue analysis in food and feed.

SFE partners with INA and other organizations to research issues and develop better pest management strategies that decrease the impact on food safety and increase environmental protection. For example, cilantro aphid infestation, tomatoes.

SFE has agreements with some large supermarket chains who promote the implementation of GAPs by requiring their suppliers to meet the requirements of a voluntary domestic certification scheme. This scheme is overseen by SFE.

SFE partnered with the Chamber of Agriculture and Farming and, with municipalities to implement the Empty Pest Container Project which promotes appropriate handling and storage of used pesticide containers. Under this project, SFE runs container collection programs.

The SFE is a member of a national Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) Commission which aims to implement tolerance limits for antibiotics and endocrine disruptors. Led by the MOH, other members include SENASA, private companies, hospitals and clinics.

8.3 National water laboratory

The LNA is the reference laboratory for microbiological and physical analysis of water. They monitor the sanitary quality of water at various sampling levels including: operators of aqueducts, wastewater treatment plants, health sector points (hospitals), restaurants, hotels, recreational sites, and other establishments.

Samples are taken by AyA's regional personnel according to an annual sampling plan for potable water quality which is developed with the MOH. AyA also conducts monitoring and sampling in the event of emergencies. All samples are tested in the San Jose laboratory. Samples are analysed for chemical and microbial contamination including viruses and parasites. Reports of results are posted publically.

Results are routinely communicated to the MOH and, the CCSS. If the aqueducts are publically owned, AyA will send workers to repair it. If it is privately owned, then AyA provides recommendations. The MOH has the authority to close aqueducts in the event of a risk to public health. Agreements are signed in instances where other ministries such as the MOH or the MAG request assistance in sampling and analysis. The MOH routinely reviews AyA's annual water quality reports.

The laboratory employs a sufficient number of well trained personnel.

The LNA is ISO 17025-accredited by ECA for 88 methods of analysis and and 2 sampling techniques.

9.0 Closing meeting

The closing meeting was held with MOH, MAG and a representative from the Canadian Embassy in Costa Rica on March 9, 2018. The CFIA team thanked the MOH and the SFE for their efforts in supporting the mission, and in their openness and transparency in facilitating understanding of Costa Rica's current food safety system. An open discussion was held to give MOH and MAG an opportunity to clarify the team's observations and recommendations. This served to reinforce the good relations that CFIA has with MOH and MAG with respect to the safety of FF that is marketed in Canada.

9.1 Observations

Several areas were highlighted where Costa Rica could further strengthen their program. These were shared with the CA during the closing meeting.

Costa Rica has a well-developed program to monitor and prevent chemical contamination and, has established general food safety requirements for the production of safe FF.

Costa Rica is working to enhance their national food safety program legislative system to strengthen government oversight and coordination by redefining the roles and responsibilities of the parties involved. They have made significant investments in laboratory capacity to support the future integrated national food safety program.

The CFIA team observed that the period of validity for the sanitary operating permit varied from 1 to 5 years depending on the type of operation. The MOH recognized inconsistencies in meeting the legal requirement (1 year).

The MOH is required to conduct an on-site inspection of the facility once the permit has been issued. However, the CFIA did not observe evidence of this. The MOH advised that they are revising their regulations to ensure inspections are conducted consistently.

Even though GMPs are the criteria used to evaluate operations with a sanitary operating permit of the operations visited, the government does not require operators to implement a food safety plan. GAPs and GMPs are the foundation for the development of a comprehensive food safety system. They do not take the place of one.

The CFIA team recognised that the MOH and the SFE are working with other partners on the Inter-sectoral Commission to develop and implement a NFSS which will provide a more integrated and coordinated approach to food safety in the future.

10.0 Conclusion and recommendations

As a result of this visit, the CFIA assessment team has established a general understanding of Costa Rica's food safety program and, a solid foundation for good working relations with the MOH and the MAG.

Costa Rica acknowledged the observations and recommendations presented by the CFIA team and expressed their future interest in collaboration.

The CFIA encourages Costa Rica to find ways to strengthen their existing legislation to require industry to implement risk-based food safety programs and, to enhance government oversight through risk-based sampling and monitoring programs.

Both the MOH and the SFE have responsibilities to conduct GMP inspections of packing operations. They could consider how they might collaborate to prevent duplication of work to better utilise resources and, reduce burden on operators by reducing the number of visits.

Annex A: Summary of the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Agriculture's action plans/ comments to the CFIA recommendations from the assessment report of Costa Rica's Food Safety Control System for Fresh Fruit

| No | CFIA Recommendation | MOH/MAG Action plans/Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify ways to strengthen existing legislation to require industry to implement risk-based food safety programs and, to enhance government oversight through risk-based sampling and monitoring programs. | Under review for adjustment of regulations. |

| 2 | Implement procedures to promote the consistency of inspections conducted by the MOH. | In the process of reviewing and updating the procedures for operational health permits. |

| 3 | Consider how the MOH and the SFE might collaborate to prevent duplication of GMP verifications in packing facilities to better utilise resources and, reduce burden on operators by reducing the number of visits. | Working on the implementation of Decree No. 27983-MAG-SALUD, which will permit us "To authorize and appoint as health inspectors, in the capacity of health authorities, professional officials and technicians of the Plant Health Service (Servicio Fitosanitario del Estado), Directorate of Animal Health (Dirección de Salud Animal) of MAG, the Production Council (Consejo de Producción (CNP)) and the Agriculture and Fisheries Integrated Marketing Program (Programa Integral de Mercadea Agropecuario (PIMA)), to allow them to perform technical functions." |

Annex B: Roles and responsibilities of the key departments involved in food safety in Costa Rica

Responsible for regulation, control and inspection

Ministry of Health

- fruit and vegetables

- microbiological testing, mycotoxins, heavy metals, antimicrobial resistance

- processed foods

Plant Health Service

- fruit and vegetables

- pests, pesticides, heavy metals, chemical by-products

Other agencies

- Costa Rican Institute of Aqueducts and Sewers

- responsible for potable water and the National Water Laboratory

- Agricultural Extension

- technical assistance and support for producers

- INCIENSA

- official food analysis laboratory of the Ministry of Health

Ministry of Economy, Industry and Commerce

- CODEX

- Technical regulations

Figure 1: Roles and responsibilities of the key departments involved in food safety in Costa Rica