ISSN: 2819-0890

On this page

Executive summary

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) is Canada's leading authority on food fraud oversight. This report shares how we prevented a significant amount of misrepresented food from being sold in Canada.

Between April 1, 2023, and March 31, 2024, we conducted a number of activities to prevent, detect and deter food fraud. Activities included:

- monitoring and analyzing risks and planning mitigation activities

- promoting awareness

- working with international counterparts

- advancing research and method development

- targeting surveillance and taking enforcement action where appropriate

We conducted 2 types of sampling during this timeframe: marketplace monitoring sampling (also referred to as targeted surveys) and targeted inspectorate sampling.

- Marketplace monitoring sampling involves samples collected by an independent third party contracted by the CFIA and occurs only at retail stores to gauge overall compliance of certain food products in the Canadian marketplace

- Targeted inspectorate sampling involves inspection and sampling by CFIA inspectors at different types of food businesses such as importers, domestic processors and retailers

- The likelihood of finding non-compliance is higher because it targets food businesses associated with risk factors such as a history of non-compliance, gaps in preventive controls or unusual trading patterns

Marketplace monitoring

Marketplace monitoring during this period included sampling and testing for authenticity and misrepresentation of:

- coconut water

- fresh meat

- spices

- sunflower oil

- tea

323 marketplace monitoring samples were assessed to detect specific types of misrepresentation through laboratory analysis. Results demonstrated high compliance, except for coconut water which was lower.

Targeted inspectorate activities

Targeted inspectorate activities during this period included inspecting, sampling, and testing for authenticity and misrepresentation of:

- fish

- honey

- meat

- olive oil

- organic fresh or frozen fruits and vegetables

- other expensive oils

- grated hard cheese

- fruit juice

- other foods

712 targeted samples were assessed to detect specific types of misrepresentation through laboratory analysis. We also conducted 345 label verifications, including basic label verifications and net quantity verifications. Overall, compliance rates were similar to previous years. Highlights include:

- grated hard cheese, olive oil and other expensive oils had the lowest satisfactory rates for authenticity testing, whereas fish, fruit juice, meat and honey had the highest

- fish, olive oil and other expensive oils had the lowest compliance rates for label verifications, while organic fresh fruit and vegetables, grated hard cheese and other foods had the highest

Note: our sampling approach changes from year to year, therefore, it's not accurate to infer food fraud trends in Canada by comparing results from different years. Program design is continually improving and this surveillance is not intended to measure overall compliance rates across the Canadian marketplace, making year-to-year comparisons unreliable.

For example, to increase the likelihood of detecting food misrepresentation, we focus our targeted inspectorate activities on higher risks. As a result, targeted inspectorate activities find higher rates of non-compliance than if they were to include all products and food businesses across the marketplace. Our ability to find food misrepresentation is continually improving, which may result in more fraud detection year after year. As such, these results are not representative of overall compliance rates within the Canadian marketplace.

Where we found non-compliance, we took control and enforcement actions, guided by the applicable regulations and the CFIA's Standard Regulatory Response Process. Control and enforcement actions included removing products from Canada and detaining, destroying or relabeling products, which prevented misrepresented food from being sold in Canada. These actions directly protected consumers from misrepresentation and allowed businesses to compete fairly in the market.

Introduction

Food fraud is a priority under the Food Policy for Canada. As part of this initiative, the CFIA addresses food misrepresentation that falls within its statutory mandate. It does this through strategies to prevent, detect and deter false, misleading or deceptive practices related to the manufacturing, preparation, labelling, selling, importing or advertising of food. Health Canada works with the CFIA on this initiative. For the purpose of this report, our work on food misrepresentation is referred to as "food fraud".

Food fraud may occur when food is misrepresented. It's an issue that has been identified around the world. In Canada, it's prohibited to sell food in a manner that is false, misleading or deceptive. Industry is responsible for properly representing and labelling food products.

We take food fraud seriously. Oversight activities center on 3 themes:

- prevent

- detect

- deter

This report summarizes the work done under each of these themes for the fiscal year April 1, 2023, to March 31, 2024. Activities described in this report are from that time period unless indicated otherwise.

Acts and regulations

Canada continues to be a leader in safe and reputable food, and its regulatory framework is highly regarded internationally. We carry out inspection, sampling, testing and enforcement activities under the following authorities:

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency Act

- Food and Drugs Act

- Food and Drug Regulations

- Safe Food for Canadians Act

- Safe Food for Canadians Regulations

Food businesses are responsible for complying with regulatory requirements and the CFIA conducts inspection activities to verify if businesses are meeting their statutory and regulatory obligations.

Prevent

For the purpose of this report, prevention means the proactive CFIA measures taken to avoid the misrepresentation of food that is produced, processed or sold in Canada.

Risk intelligence, analysis, and program design

As in previous years, we continue to analyze inspection and sampling results as well as intelligence about misrepresentation risks in Canada to identify suitable activities to mitigate these risks. Program design work is continually improved to respond to areas of highest impact, including emerging risks.

Key activities included compiling and analyzing the following types of information:

- monthly situational awareness reports

- intelligence reports on juices and coconut water, mixed spices, and shrimp, crustaceans and scallops

- an environmental scan of scientific methods for detecting food fraud

The CFIA and Health Canada continue to combine their situational awareness and environmental scanning work. This year's activities focused on exploring issues affecting the food supply that could introduce food fraud vulnerabilities and identifying priority areas for monitoring activities in the Canadian context.

We also engaged with industry associations and partners about the possibility of establishing a Food Industry Intelligence Network (FIIN) in Canada, similar to the model established in the United Kingdom (UK). The UK FIIN model is led by the food industry. Members of the network generate anonymized data that is shared between its members and with regulators. This sharing of information can improve understanding of food fraud risks in the supply chain. It is a proactive way to mitigate those risks, which are part of industry's responsibility to maintain preventive controls and ensure compliance. Activities included:

- facilitating a virtual presentation with FIIN organizers from the UK that 55 Canadian industry representatives attended

- seeking stakeholder feedback on the UK model, including whether there was interest in establishing a similar model in Canada

- engaging with other federal government departments regarding funding and competition considerations

While some stakeholders saw value in a model similar to FIIN in Canada, industry has not indicated any immediate plans to establish something similar in Canada at this time.

Using a questionnaire, we also consulted with the provinces and territories to better understand food misrepresentation-related activities and authorities at that level. This information will be used to identify potential areas of collaboration between federal and provincial and territorial partners.

Promoting awareness

This year, we focused on raising awareness and understanding with consumers and industry, in these areas:

- what food fraud is

- what their roles are in detecting and preventing it

- how to report a concern

- fish and seafood labelling and traceability

Social media

We posted 76 posts about food fraud on our social media channels to share information and build awareness. Platforms included Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and X.

Posts received 228,595 impressions (the number of times the post was displayed to users) and 8,251 engagements (such as likes, shares, comments and clicks). The majority of the engagements came from reactions and link clicks. This topic received genuine interest with positive to neutral interactions.

Web improvements and performance

We created a Fish and seafood labelling and traceability topic page to raise awareness of how we work to verify that fish sold in Canada is safe and accurately labelled. It received 549 visits between December 14, 2023 and March 31, 2024.

The remaining web content related to food fraud received more than 35,000 visits this fiscal year.

Media outreach

Campaigns that launched in previous years continued to be picked up this year by media outlets across Canada. Articles and radio spots were used 557 times throughout the year. The combined reach for the various outlets was more than 2.1 million people. These campaigns were aimed at informing consumers about the impact of food fraud, as well as what they can do if they suspect their food is misrepresented.

Public opinion research

We held 8 focus groups and did telephone surveys to get opinions from 1,500 consumers and 1,130 businesses on a variety of topics related to food safety, including food fraud.

When comparing these results to the 2022 public opinion research, we learned that people are less concerned about food fraud (66% indicated a great deal/some concern in 2024 versus 76% in 2022). For the most part, participants felt that food fraud is well managed in Canada. There was a high level of confidence that food in Canada is safe to eat. We also found that people are more likely to report food fraud to the CFIA (61% would report to the CFIA in 2024 versus 53% in 2022).

Media monitoring

As part of our research and analysis, we regularly conduct media monitoring on food fraud to allow us to better understand the needs and concerns of consumers and industry so that we can improve programs and services.

International collaboration

We continued to reach out to our foreign counterparts to provide information on non-compliant products originating from their jurisdiction and raise awareness of potential food fraud situations. This included sending 9 letters to foreign competent authorities to share details on 55 non-compliance issues. In several instances, foreign competent authorities shared the details of their follow up actions and findings, as well as information on the programs and activities they have in place to combat food fraud in their own territory. These efforts contribute to preventing food fraud in foods imported into Canada.

We continued our active involvement in the Global Alliance on Food Crime, a coalition of food authorities from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. Members of the Global Alliance have agreed to work together to prevent, detect and disrupt food fraud, which collectively increases our impact, given the global nature of food supply chains. Members have established terms of reference, drafted a workplan and started working on joint activities. This partnership allows Canada to contribute and benefit from information sharing, expertise, best practices and coordinated activities.

Finally, our technical experts delivered seminars to foreign trading partners from the Indo-Pacific region and the Americas about the Canada Organic Regime and our approach to prevent and control food fraud. This outreach fosters international cooperation to combat food fraud and contributes to increasing the compliance of imported foods with Canadian requirements.

Detect

For the purpose of this report, detect means the active determination of food fraud occurring.

We detect food fraud through activities such as:

- inspecting

- reviewing documentation and records

- conducting label verifications

- doing net quantity verifications

- sampling and testing

Methodology research and development

The CFIA and Health Canada continue to develop new analytical methods to detect food fraud and product misrepresentation and improve current ones.

This year, we completed preliminary studies to identify a DNA based analytical method for meat speciation which will enhance the ability to identify and quantify meat species adulteration and substitution in cooked and uncooked meat products.

We also continued research for:

- tuna speciation: method development and validation of DNA barcoding for tuna species

- high value oils: expanding the capacity for testing and evaluating additional high value oils for authenticity

Each year, we evaluate if there are any gaps in available techniques to detect food fraud, often related to emerging issues and develops research needs and priorities based on this information. This year, research began on these projects:

- turmeric authenticity (started and completed): development of a rapid, non-targeted method to detect specific adulterants used as colours and bulking agents in ground turmeric using infrared and atomic emission spectroscopy

- saffron authenticity: using genomics and non-targeted methods to identify saffron and distinguish it from its common adulterants

- alcoholic beverage adulteration: development of a method to detect and quantify adulteration of alcoholic beverages using a small molecule analytic method

- coffee and tea adulteration: development of a genomics method to detect substitution and adulteration in coffee and tea

Initially reported in the Food Fraud Annual Report 2021 to 2022 and Food Fraud Annual Report 2022 to 2023, Health Canada continues to lead 3 multi-year research projects:

- a proteomics project for authentication of ground spices

- a small-molecule chemometrics project for beverage authentication

- a proteomics project to test for authenticity of plant-based protein sources

The proteomics project on ground spices has progressed, and peptide spectral libraries have been created for saffron and common plant adulterants. These were used to develop a targeted method to detect saffron proteins and some typical substitutions.

The small-molecule chemometrics project has also progressed and a non-targeted method for pomegranate juice authentication was developed to determine substitution with other juices (for example, grape, apple and pear juices).

The proteomics project to test for authenticity of plant-based protein sources has also progressed. The goal is to detect and differentiate between unlabelled legume and bean sources used as fillers in meat and vegan products that could pose a risk for allergic consumers. Spectral libraries have been created for common legumes and beans and these libraries were used to select peptide markers for developing a targeted method.

Verifying organic products

Anyone who suspects a violation of the Canada Organic Regime (COR) (for example, fraudulent organic claims or activities) may contact the CFIA to submit a complaint. This year, the CFIA's COR team received 20 complaints:

- 17 were against operators holding certification under the COR scope

- 2 were against a CFIA-accredited certification body

- 1 was against a former organic product certificate holder

We have successfully resolved 18 complaints and work is ongoing on the remaining 2.

As reported in the Food Fraud Annual Report 2021 to 2022, we continue to update the Automated Import Reference System (AIRS) to capture more information about how organic products are entering Canada. This will also allow for more efficient validation of organic certificates at the time of import. We will notify importers when import requirements are incorporated into AIRS. After that, importers of organic food commodities will be required to submit a digital copy of the organic product certificate when declaring organic products online, using the Integrated Import Declaration system. For updates on this work, refer to COR import requirements.

We conducted 46 basic label verifications of organic claims made on organic fresh or frozen fruit and vegetables. Results indicated a 98% (45/46) compliance rate. These basic label verifications were done on both domestic and imported products, and included foods such as blueberries, carrots, cucumbers, mushrooms, tomatoes, mango, oranges and strawberries. The one non-compliant result was for beets imported from the Netherlands.

CFIA-accredited certification bodies also conducted activities including certification and other forms of oversight under the COR. Activities included label and documentation reviews, as well as planned and unannounced inspections.

Surveillance: inspection, sampling, testing and results

We track, monitor and analyze the data and results of our food misrepresentation work from year to year. We design our food fraud surveillance to target high-risk products by using previous findings to increase the likelihood of detecting food misrepresentation. It is not possible to say whether food fraud in Canada is on the rise or decline by simply comparing results with previous years. Program design is continually improving and this surveillance is not intended to measure overall compliance rates across the Canadian marketplace, making year-to-year comparisons unreliable. For example, the current food fraud report found that 94% of meat tested did not indicate species substitution versus 98% the year before. These 2 data sets are not enough to conclude that misrepresentation of meat species is on the rise in Canada, as other parameters changed, such as enhanced targeting of samples.

Based on this year and previous years' results, as well as other sources of intelligence, we continue to refine our food fraud activities to more effectively mitigate risks. Results of targeted sampling are not representative of overall compliance in the Canadian marketplace.

For the purpose of reporting unsatisfactory sample results, we used the declared country of origin in most situations. In other circumstances, the dealer location provided on the label (that is, the location of the company responsible for the product in Canada) was used when:

- the county of origin is not a requirement and is not declared on the label

- documentation to support the country of origin was not available during inspection

- we determined that the cause of the non-compliance occurred at a point in the supply chain other than the country of origin

Regardless of the sampling location, practices leading to non-compliance may have occurred at various points of the supply chain (for example, in the originating country, during processing, packaging/repackaging in Canada). So an unsatisfactory result may not always mean the issue originated in the exporting country or where product was sampled.

Results are rounded to the nearest whole number.

Sampling and testing

During the 2023 to 2024 year, we conducted 2 types of sampling to detect food misrepresentation in Canada:

- marketplace monitoring

- targeted inspectorate sampling

Marketplace monitoring

Marketplace monitoring (also sometimes referred to as targeted surveys) involves sampling by an independent third party under contract with the CFIA. The third party collects samples of prepackaged products sold to consumers at retailers in various cities across Canada. Samples are then tested by the CFIA and the results are used to gauge compliance in the Canadian marketplace, as well as to inform future activities.

We used environmental scanning to identify areas of vulnerability to fraud and misrepresentation, and then did marketplace monitoring to detect food misrepresentation in the following commodities:

- coconut water adulterated with added water, foreign sugars and/or casein

- fresh meat containing (undeclared) sulfites to alter appearance

- single and mixed ground spices adulterated by the addition of colours or dyes

- sunflower oil substituted or diluted with other oils

- tea adulterated by the addition of colours or dyes

Coconut water

We conducted marketplace monitoring to verify the authenticity of coconut water by testing for the addition of water, foreign sugars and/or casein.

Results indicated that:

- 79% of the samples were satisfactory (30/38)

- of the 21% that were not satisfactory (8/38)

- 5% were unsatisfactory due to the detection of casein (2/38)

- 16% were investigative due to the detection of foreign sugars (6/38)

The Codex General Standard for Fruit Juices and Nectars (PDF) (CXS 247-2005) prohibits the addition of foreign sugars to coconut water. The presence of casein (a milk protein) also indicates adulteration and can pose a health risk to consumers with allergies when not declared on the label.

Of the 8 samples that were not satisfactory, these were the declared origin:

- Thailand (4)

- Viet Nam (4)

Methodology: chemical characterization of coconut water by determination of:

- soluble solids by refractometer

- sugars by ultra-performance liquid chromatography

- δ13C (Delta 13C) by cavity ring-down spectroscopy

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay that detects casein

Sample type:

- coconut water

Fresh meat

We conducted marketplace monitoring to test meat for the non-permitted addition of sulfites, a food additive that can restore red colouration of meat and enhance the appearance of product freshness.

Results indicated that 100% of samples were satisfactory (69/69).

Methodology: detection of sulphites in fresh meat by the:

- Optimized Monier-Williams Method

Sample type:

- fresh (unfrozen) ground meat (beef, pork, chicken, turkey)

- "meat patties"

- "meatballs"

- whole muscle cuts

- sub-primal cuts of meat

Spices

We conducted marketplace monitoring to verify the authenticity of single and mixed ground spices by testing for the presence of colours or dye.

Results indicated that:

- 94% of the samples were satisfactory (94/101)

- 6% were unsatisfactory (7/101)

Of the 7 spice samples that were unsatisfactory, indicating the presence of non-permitted colours or colours beyond the levels permitted in the regulations, these were the declared origin or dealer location:

- Canada (1 curry, 1 garam masala, 2 tandoori masala)

- India (1 tandoori masala)

- Islamic Republic of Iran (1 cayenne pepper)

- Pakistan (1 tandoori masala)

Methodology:

- fat-soluble colours by high performance liquid chromatography

- water-soluble colours by high performance liquid chromatography

Sample type:

- cayenne pepper

- cinnamon

- cumin

- curry

- garam masala

- turmeric

- other spices

Sunflower oil

We conducted marketplace monitoring to detect substitution or dilution of sunflower oil with other oils. It was estimated that in 2021, approximately 50% of the global export of sunflower oil came from Ukraine (PDF). Our intelligence on the potential impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on the Canadian food supply indicated the possibility of supply chain challenges for sunflower oil. The survey was conducted to determine if such supply chain challenges may have resulted in adulterated sunflower oil in Canada.

Results indicated that 100% of the samples were satisfactory (19/19).

Methodology:

- gas chromatography to assess sterol and fatty acid profile

Sample type:

- sunflower oil

Tea

We conducted marketplace monitoring to verify the authenticity of tea by testing for the presence of colours or dyes.

Results indicated that:

- 99% of the samples were satisfactory (95/96)

- 1% was unsatisfactory (1/96)

The unsatisfactory (adulterated) sample was a fermented tea with a declared origin of Hong Kong.

Methodology: chemical characterization of tea by determination of:

- fat-soluble colours by high performance liquid chromatography

- water-soluble colours by high performance liquid chromatography

Sample type:

- tea with a compositional standard, including tea, black tea, and green tea

Targeted inspectorate sampling and label verifications

In this report, targeted inspectorate sampling means sampling by CFIA inspectors at the regulated party that is responsible for the product in Canada. This includes domestic processors, importers or in the case of foods prepared, packaged and labelled at retail, retailers. Unlike marketplace monitoring, this sampling targets areas of higher risk, based on factors such as history of non-compliance, unusual trading patterns and gaps in preventive controls. Results are not representative of overall compliance rates within the Canadian marketplace.

As part of our targeted inspectorate sampling, we also conducted targeted label verifications. For the purposes of this report, label verifications include basic label verifications and net quantity verifications.

- A basic label verification is an assessment of the food label to determine compliance with regulatory requirements including:

- common name

- list of ingredients

- claims

- traceability information

- country of origin

- any other mandatory or voluntary label information

- Net quantity verification is an assessment of the accuracy of the net quantity declared on the food label

We conducted this surveillance for the following types of food misrepresentation:

- fish species substitution

- honey adulterated with added sugars

- meat species substitution

- olive oil adulteration

- adulteration of other expensive oils

- grated hard cheese adulterated with anticaking agents above permitted levels

- fruit juices substituted or diluted with other or lower value juices, water or the addition of foreign sugars or acids

- mislabelled or short weight food (when the product weighs less than declared)

Surveillance that we did in previous years is summarized in these reports:

- Report: Enhanced honey authenticity surveillance (2018 to 2019)

- Report: Honey authenticity surveillance results (2019 to 2020)

- Report: Enhanced fish species substitution surveillance (2019 to 2020)

- Report: Food Fraud Annual Report 2020 to 2021

- Report: Food Fraud Annual Report 2021 to 2022

- Report: Food Fraud Annual Report 2022 to 2023

Summary of infographic: description of results

A total of 712 targeted samples assessed for authenticity amongst 7 commodities:

- Fish: 92% satisfactory

- Honey: 88% satisfactory

- Meat: 94% satisfactory

- Olive oil: 76% satisfactory

- Other expensive oils: 76% satisfactory

- Grated hard cheese: 55% satisfactory

- Fruit juices: 95% satisfactory

CFIA took appropriate action when it found non-compliance.

By conducting this surveillance work, we prevented misrepresented food from being sold in Canada. For example, lower value food labelled as a higher value product or with its cost inflated due to a lower amount of food in the package than declared in the net quantity. Activities outlined above directly protected consumers from unfair practices.

Samples do not represent the totality of our food testing activities. Each year, in addition to sampling and testing for food fraud, we conduct tens of thousands of tests under various surveillance programs to detect allergens, chemical hazards, and microbiological hazards. Reports detailing the results of food safety surveillance activities in Canada are also published.

Targeted inspectorate sampling

Fish

We conducted sampling to detect fish species substitution (this means the species declared on the label is substituted with another, usually less expensive, species).

Figure 1: Results from sampling to detect fish species substitution

Text version - Figure 1

- 92% of the results were satisfactory (70/76)

- 8% were unsatisfactory (6/76)

3 additional samples were taken but given no decision. Those samples could not be assessed because a DNA barcode could not be generated for various reasons (for example, due to DNA degradation or fish cross-contamination).

Methodology: DNA barcoding to identify the fish species and compare it with the species associated with the declared common name, according to the CFIA Fish List

Sample type: prepackaged fish filets in fresh, frozen, dried, or salted format. Species most likely to be substituted:

- cod

- halibut

- kingfish

- mackerel

- pollock

- sea bass

- snapper (red and other)

- sole

- tuna

- yellowtail

We also sampled other types of fish suspected to be substituted or mislabelled.

Where sampling occurred:

- domestic processors

- importers

- retailers

Figure 2: Compliance results by sampling location

Text version - Figure 2

- Domestic processors: 100% were satisfactory (13/13)

- Importers: 87% were satisfactory (27/31)

- Retailers: 94% were satisfactory (30/32)

Of the 6 fish samples that were unsatisfactory for fish species substitution:

- 2 were packaged and labelled at retail:

- 1 was imported product from the United States (labelled as kingfish)

- 1 was a domestic product (labelled as red snapper)

- 4 were imported products that were prepackaged in the country of origin or foreign state of origin:

- Viet Nam (1 labelled as red snapper)

- China (1 labelled as southern blue whiting and 1 labelled as yellowfish sole)

- Chinese Taipei (1 labelled as narrow-barred Spanish mackerel)

The 70 satisfactory samples included 32 fish species such as cod, halibut and pollock.

It's mandatory to declare the country of origin on the label of imported prepackaged fish.

View the results on the Open Government Portal for Fish.

Fruit juices

We conducted sampling to detect adulteration of fruit juices. Adulteration of fruit juice can occur when foreign sugars, acids or dyes are added, the juice is diluted with water or some of it is substituted with less expensive juice(s).

Figure 3: Results from sampling to detect fruit juices adulteration

Text version - Figure 3

- 95% of the results were satisfactory (135 out of 143)

- 4% were unsatisfactory (7 out of 143)

- 1% was investigative (1 out of 143)

1 pomegranate juice sample was assessed as investigative because the soluble solids were below the requirement.

Methodology: chemical characterization of fruit juices by determination of:

- soluble solids by refractometer

- minerals by inductively coupled plasma spectrometry

- organic acids and preservatives by high performance liquid chromatography

- sugars by ultra-performance liquid chromatography

- δ13C (Delta 13C) by cavity ring-down spectroscopy

- d-malic acid by enzymatic assay (for apple and pomegranate juice)

- determination of water-soluble colours by high performance liquid chromatography

Sample type:

- fruit juices, not including blends of juices 'cocktail' or 'drink' mixes with added sugar, water or flavour

Where sampling occurred:

- domestic processors

- importers

- retailers

Figure 4: Compliance results by sampling location

Text version - Figure 4

- Domestic processors: 97% were satisfactory (29/30)

- Importers: 94% were satisfactory (101/107)

- Retailers: 100% satisfactory (5/5)

Of the 7 fruit juice samples that were unsatisfactory, indicating adulteration, these were the declared origin:

- Canada (1 orange juice)

- Greece (1 lemon juice and 1 lime juice)

- Italy (1 lime juice)

- Türkiye (2 pomegranate juices)

- United States (1 pomegranate juice)

The 135 satisfactory samples included 17 types of fruit juices such as apple, blueberry, cherry, cranberry, grape, pineapple and raspberry.

It's mandatory to declare the country of origin on the label of imported prepackaged fruit juice.

View the results on the Open Government Portal for fruit juices.

Grated hard cheese

We conducted sampling of grated hard cheese to detect potential excess use of cellulose. Cellulose is a food additive that can be used legally as an anti-caking agent, but when present beyond permitted levels, is considered an adulterant. The practice of adding excess cellulose as a filler is fraudulent and results in financial loss for consumers who are paying for excess cellulose at the cost of cheese.

Figure 5: Results from sampling to detect grated hard cheese adulteration

Text version - Figure 5

- 55% of the results were satisfactory (29 out of 53)

- 45% were unsatisfactory (24 out of 53)

Methodology: determination of total dietary fibre by the rapid enzymatic-gravimetric method

Sample type:

- parmesan

- romano

- asiago

- grana padano

- manchego

- blends of the above

Where sampling occurred:

- domestic processors

- importers

- retailers

Figure 6: Compliance results by sampling location

Text version - Figure 6

- Domestic processors: 50% were satisfactory (16/32)

- Importers: 64% were satisfactory (9/14)

- Retailers: 57% were satisfactory (4/7)

Of the 24 grated hard cheese samples that were unsatisfactory, indicating excess use of cellulose:

- 16 were packaged and labelled at a domestic processor

- 14 Parmesan, 1 Romano and 1 blend of Asiago, Romano and Parmesan

- 5 were imported products packaged and labelled in the country of origin

- United States (3 Parmesan, 1 Romano and 1 blend of Asiago, Romano and Parmesan)

- 3 were packaged and labelled at retail

- 3 Parmesan

The 29 satisfactory samples included 8 types of hard grated cheese including Asiago, Parmigiano Reggiano and Romano.

Health Canada reviewed the results and did not identify food safety concerns with the levels of cellulose found in the unsatisfactory samples.

It's mandatory to declare the country of origin on the label of imported prepackaged dairy products.

View the results on the Open Government Portal for grated hard cheese.

Honey

We conducted sampling to detect misrepresentation of honey adulterated with foreign sugars (such as those derived from sugar cane, corn syrups or rice syrups) in both domestic and imported honey sold in Canada.

Figure 7: Results from sampling to detect honey adulteration with foreign sugars

Text version - Figure 7

- 88% of the results were satisfactory (74 out of 84)

- 12% were unsatisfactory (10 out of 84)

Methodology:

- detection of C4 and C3 sugars by nuclear magnetic resonance

- detection of C4 sugars by stable isotope ratio analysis

Sample type:

- prepackaged

- bulk

- blends from multiple sources

Where sampling occurred:

- domestic processors

- importers

Figure 8: Compliance results by sampling location

Text version - Figure 8

- Domestic processors: 94% were satisfactory (15/16)

- Importers: 87% were satisfactory (59/68)

Of the 10 honey samples that were unsatisfactory for the presence of foreign sugar, these were the declared origin:

- Canada (1)

- Egypt (1)

- France (1)

- Greece (1)

- India (2)

- Islamic Republic of Iran (1)

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (1)

- Blend from Brazil, Canada, India, Mexico, United States and Uruguay (1)

- Blend from India, United States, Uruguay and Viet Nam (1)

It's mandatory to declare the country of origin on the label of honey.

View the results on the Open Government Portal for Honey.

Meat

We conducted sampling to detect the substitution of meat species (typically with lesser value species than what is declared) in raw and heat-treated meat.

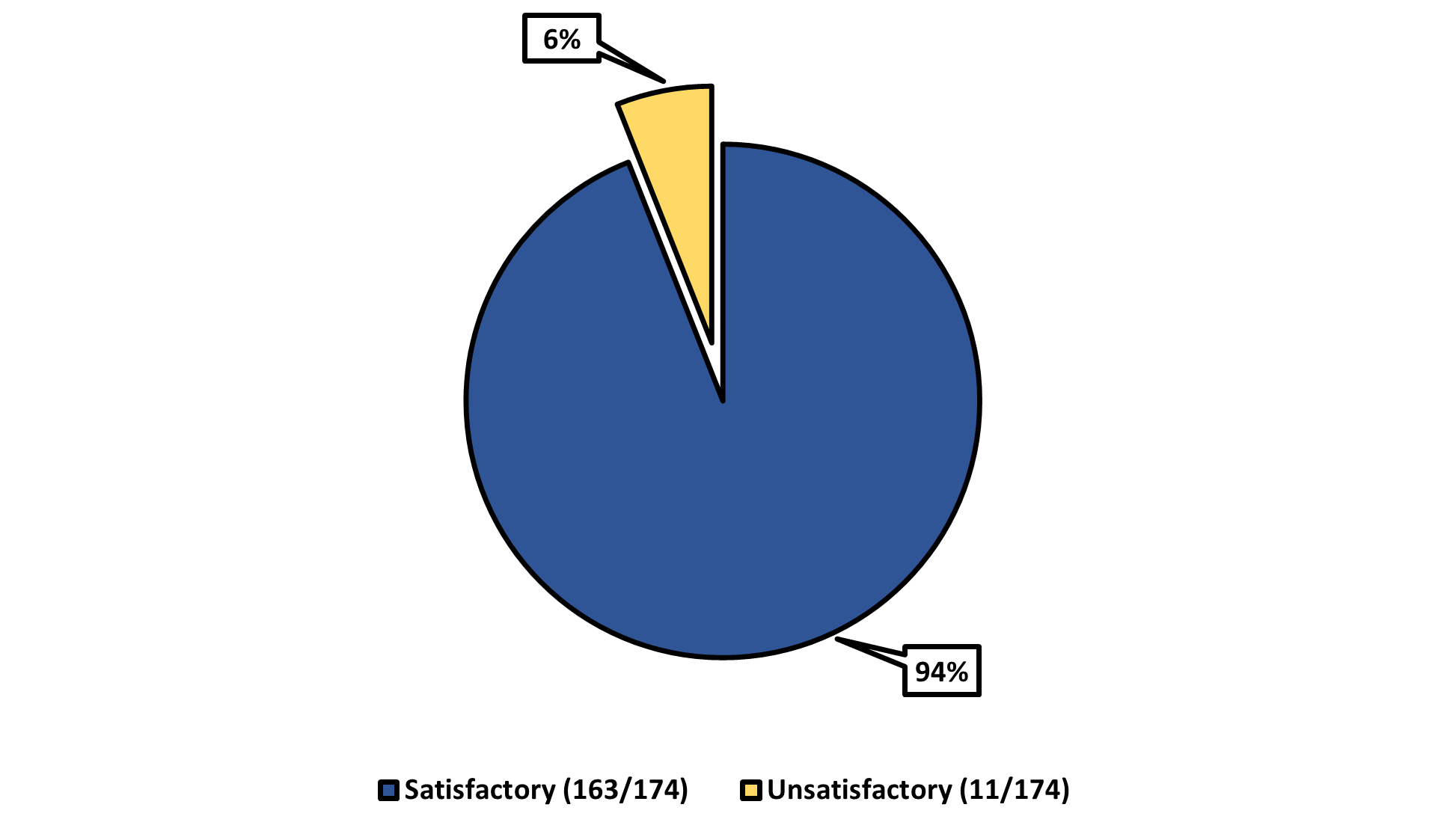

Figure 9: Results from sampling to detect meat species substitution

Text version - Figure 9

- 94% of the results were satisfactory (163/174)

- 6% were unsatisfactory (11/174)

3 additional meat samples were taken but given no decision. These samples could not be assessed because the way the product was processed interfered with the testing.

Methodology:

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay that detects species-specific antibodies

Sample type:

- raw and ready-to-eat meat products ground or cut up (comminuted) to a degree that the species cannot be determined by eyesight

Where sampling occurred:

- domestic processors

- importers

- retailers

Figure 10: Compliance results by sampling location

Text version - Figure 10

- Domestic processors: 99% were satisfactory (93/94)

- Importers: 100% were satisfactory (34/34)

- Retailers: 78% were satisfactory (36/46)

Of the 11 samples that were unsatisfactory for meat species substitution:

- 10 were domestic products packaged and labelled at retail:

- 5 ground beef, 2 ground lamb, 2 ground pork and 1 ground turkey

- 1 was a domestic product packaged and labelled at the processor:

- 1 ground blend of chicken, pork and turkey

The 163 satisfactory samples included 13 different meat species combinations, including: beef, beef and veal, bison, pork and pork and duck.

It's mandatory to declare the country of origin on the label of imported meat products.

Root cause analysis of the unsatisfactory sample results identified a range of issues, including unintentional cross-contamination and absence of species declared on the label.

View the results on the Open Government Portal for Meat.

Olive oil

We conducted sampling to detect misrepresentation of olive oil adulterated with lower value oils, including misrepresentation of claims such as "extra virgin", "virgin", "cold pressed" and "unrefined".

Figure 11: Results from sampling to detect olive oil adulteration

Text version - Figure 11

- 76% of the results were satisfactory (70/92)

- 24% were unsatisfactory (22/92)

Methodology:

- gas chromatography to assess sterol and fatty acid profile, as well as stigmastadiene content

Sample type:

- extra virgin oil

- virgin olive oil

- olive oil composed of refined and extra virgin olive oils

Where sampling occurred:

- importers

- domestic blenders

- packers or bottlers

- bulk oil distributors

Figure 12: Compliance results by sampling location

Text version - Figure 12

- Domestic processors: 14% were satisfactory (1/7)

- Importers: 81% were satisfactory (69/85)

Of the 22 olive oil samples that were unsatisfactory, indicating adulteration or misrepresentation, these were the declared origin or dealer locations:

- Algeria (1 virgin olive oil)

- Greece (4 extra virgin olive oils)

- Italy (1 extra virgin olive oil)

- Lebanon (3 extra virgin olive oils)

- Morocco (1 extra virgin olive oil)

- Republic of Korea (1 extra virgin olive oil)

- Spain (1 extra virgin olive oil)

- Tunisia (1extra virgin olive oil)

- Türkiye (2 extra virgin olive oils)

- Blend of Greece, Italy and Spain (1 extra virgin olive oil)

- Canada (6 extra virgin olive oils)

- These 6 results are identified by the Canadian licence holder responsible for the product, even though Canada does not produce olive oil. This is because either the misrepresentation was determined to occur in Canada, or because country of origin information was not declared on the label

The 69 satisfactory samples included olive oil, extra virgin olive oil, virgin olive oil and a blend of virgin olive oil and olive oil.

It's not mandatory to declare the country of origin on the label of olive oil. But a company may choose to do so voluntarily, as long as it's truthful and not misleading. When a food is wholly manufactured outside of Canada, the label must indicate that the food is imported.

View the results on the Open Government Portal for Oils.

Other expensive oils

We conducted sampling to detect substitution or dilution of expensive oils with lower value oils, including misrepresentation of claims such as "virgin", "cold pressed" and "unrefined".

Figure 13: Results from sampling to detect expensive oil adulteration

Text version - Figure 13

- 76% of the results were satisfactory (68/90)

- 24% were unsatisfactory (22/90)

Methodology:

- gas chromatography to assess sterol and fatty acid profile, as well as stigmastadiene content

Sample types:

- almond oil

- avocado oil

- coconut oil

- flaxseed oil

- grapeseed oil

- hazelnut oil

- sesame seed oil

- sunflower oil

- walnut oil

Where sampling occurred:

- importers

- domestic blenders

- packers

- bottlers

- bulk distributors

Figure 14: Compliance results by type of oil declared on the label

Text version - Figure 14

- Avocado oil: 10 out of 13 were satisfactory

- Coconut oil: 12 out of 24 were satisfactory

- Grapeseed oil: 7 out of 10 were satisfactory

- Hazelnut oil: 2 out of 3 were satisfactory

- Sesame oil: 22 out of 25 were satisfactory

Of the 22 expensive oil samples that were unsatisfactory, indicating adulteration or misrepresentation, these were the declared origin or dealer locations:

- Chile (1 grapeseed oil)

- France (1 avocado oil, 1 coconut oil, 1 hazelnut oil, 2 sesame oil)

- United Kingdom (2 coconut oil)

- United States (1 coconut oil)

- India (1 sesame oil)

- Italy (1 grapeseed oil)

- Korea (1 grapeseed)

- Pakistan (1 coconut oil)

- Philippines (7 coconut oil)

- Spain (2 avocado oil)

The 68 satisfactory samples included 12 types of expensive oil such as: almond oil, flaxseed oil and walnut oil.

It is not mandatory to declare the country of origin on oils labels. But a company may choose to do so voluntarily, provided it is truthful and not misleading. When a food is wholly manufactured outside of Canada, the label must indicate that the food is imported.

View the results on the Open Government Portal for Oils.

Basic label verification

During the 2023 to 2024 year, we conducted basic label verifications to detect misrepresentation by verifying compliance with legislative requirements, including:

- mandatory labelling

- composition

- claims

- country of origin declared on the label

Inspectors targeted businesses where the likelihood of finding non-compliance is higher based on risk factors such as a history of non-compliance, gaps in preventive controls or unusual trading patterns. Basic label verifications were performed at different types of food businesses, including importers, domestic processors and retailers.

Fish

We conducted 60 label verifications of fish and seafood products at importers, domestic processors and retailers.

Figure 15: Results from label verification of fish and seafood

Text version - Figure 15

- 73% of the label verifications were compliant (44/60)

- 27% were non-compliant (16/60)

5 non-compliances were related to misrepresentation of the common name, country of origin, and false claims. We also found 11 other labelling non-compliances, such as missing or incorrect mandatory information, infractions in the Nutrition Facts table and undeclared egg (resulting in a food recall).

Of the 16 non-compliant fish and seafood labels:

- 4 were packaged and labelled at a domestic processor, of which:

- 1 was domestic product (1 California roll)

- 3 were imported products (1 lobster,1 ocean perch, 1 Pacific cod)

- 12 were imported products packaged and labelled in the country of origin (1 abalone, 3 Atlantic salmon,1 catfish, 1 fish sauce, 1 fish ball, 1 kingfish mackerel, 1 oyster, 1 squid,1 tuna and 1 snakehead fish)

The 44 compliant labels included 29 species such as basa, pickerel and sole.

Grated hard cheese

We conducted 29 label verifications of hard grated cheese products at importers and domestic manufacturers, packagers and labellers.

Figure 16: Results from label verification of grated hard cheese

Text version - Figure 16

- 83% of the label verifications were compliant (24/29)

- 17% were non-compliant (5/29)

One non-compliance was due to misrepresentation of the country of origin declaration. We also found 4 other non-compliances, such as mandatory information missing or not shown in both official languages, and infractions in the Nutrition Facts table.

Of the 5 non-compliant grated hard cheese labels:

- 1 was packaged and labelled at a domestic processor (1 Parmesan)

- 1 was packaged and labelled at retail (1 Parmigiano Reggiano)

- 3 were imported products packaged and labelled in the country of origin (2 Parmesan, 1 Grana Padano)

The 24 compliant results included 8 types of grated hard cheeses such as Asiago, Parmesan and Romano.

Olive oil

We conducted 31 label verifications of olive oils at importers and domestic packagers and labellers.

Figure 17: Results from label verification of olive oil

Text version - Figure 17

- 68% of the label verifications were compliant (21/31)

- 32% were non-compliant (10/31)

5 non-compliances were related to misrepresentation of the common name, country of origin and false claims. We also found 5 other labelling non-compliances, such as missing or incorrect mandatory information, infractions in the Nutrition Facts table and missing bilingual label.

All 10 non-compliant labels were imported products labelled as extra virgin olive oil.

The 21 compliant labels included olive oil, extra virgin olive oil and virgin olive oil.

Other expensive oils

We conducted 37 label verifications of expensive oils at importers and domestic processors, packagers and labellers.

Figure 18: Results from label verification of expensive oils

Text version - Figure 18

- 68% of the label verifications were compliant (25/37)

- 32% were non-compliant (12/37)

8 non-compliances were related to misrepresentation of the common name, country of origin and false claims. We also found 4 other labelling non-compliances, such as missing or incorrect mandatory information, infractions in the Nutrition Facts table and missing bilingual label.

Of the 12 non-compliant expensive oils labels:

- 2 were imported products packaged and labelled at a domestic processor (2 coconut oil)

- 10 were imported products packaged and labelled in the country of origin (1 avocado oil, 5 coconut oil, 1 grapeseed oil, 1 palm oil, 1 red palm oil and 1 sesame oil)

The 25 compliant labels included 8 types such as avocado, coconut and sesame oil.

Other foods

We conducted 33 label verifications of other foods (such as nuts, olives, syrup and coffee) at importers, domestic manufacturers, packagers and labellers, and retailers that prepare, package or label foods.

Figure 19: Results from label verification of other foods

Text version - Figure 19

- 85% of the label verifications were compliant (28/33)

- 15% were non-compliant (5/33)

One non-compliance was due to a misleading common name. We also found 4 other non-compliances related to mandatory information missing or not shown in both official languages, and infractions in the Nutrition Facts table.

Of the 5 non-compliant labels:

- 2 were prepackaged domestic products (1 plant-based seafood substitute, 1 all-beef wiener)

- 2 imported products packaged and labelled in the country of origin (1 agave syrup,1 kalamata olives)

- 1 was an imported product packaged and labelled at retail (feta cheese)

The 28 compliant labels included 25 different types of foods such as cheese, meat, fruit juices, fruits and vegetables and coffee.

Net quantity verification

CFIA inspectors also conducted net quantity verifications to detect misrepresentation at different types of food businesses in Canada, including importers, domestic processors and retailers. Inspectors targeted businesses where the likelihood of finding non-compliance was higher based on risk factors such as a history of non-compliance, gaps in preventive controls or unusual trading patterns.

Fish

We conducted 95 net quantity verifications on fish and seafood at importers, domestic processors and retailers.

Fish and seafood can be uniquely vulnerable to net quantity violations due to their high value and the opportunity for excessive use of ice or water on frozen glazed products, which can lead to a falsely increased declared net weight. The net weight of frozen glazed fish and seafood is required to be declared without the weight of any ice or water (for example, "glaze"). When ice or water is included, the financial impact to consumers can be significant.

Figure 20: Results from net quantity verification of fish and seafood

Text version - Figure 20

- 76% of the net quantity verifications were compliant (72/95)

- 24% were non-compliant (23/95)

Compliance rates for fish and seafood net quantity verification by the location where the inspection was conducted are as follows:

- Domestic processors: 89% were compliant (31/35)

- Importers: 78% were compliant (21/27)

- Retailers: 61% were compliant (20/33)

Of the 23 fish and seafood samples with a non-compliant net quantity:

- 4 were domestically processed, packaged and labelled (1 wild sockeye salmon, 1 herring, 2 lobster)

- 6 were imported products packaged and labelled in the country of origin (2 basa, 1 lobster, 1 shrimp, 1 snakehead, 1 sprat)

- 13 were packaged and labelled at retail, of which:

- 4 were imported (2 cod, 1 milkfish, 1 shrimp)

- 7 were domestic (2 lobster, 1 pollock, 3 Atlantic salmon, 1 shrimp)

- 2 had an unknown country of origin (1 herring, 1 sole)

The remaining 72 verifications were compliant and included 37 fish species such as cod, halibut and pollock.

Other foods

We also conducted 14 net quantity verifications of other foods (such as cheese, meat and nuts) that were prepared, packaged or labelled at retail establishments. Results indicated that 13 net quantity verifications (93%) were compliant, while 1 (7%) was non-compliant. The 1 non-compliant sample was a striploin steak of domestic origin that was packaged at retail. The 13 compliant samples included 12 different types of food such as almonds, beef ribs and aged cheddar.

Deter

For the purpose of this report, deterring means responding to a detected non-compliance through enforcement action. It also means deterring future non-compliance, by actions such as publishing the results of enforcement activities.

Enforcement

Regulated parties are reminded of their obligations to comply with regulatory requirements. In cases of non-compliance, enforcement actions are guided by the Standard Regulatory Response Process and are considered on a case-by-case basis. We take into consideration the harm caused by the non-compliance, the compliance history of the regulated party and whether there was an intent to violate federal requirements or negligence.

We publish the outcome of a number of compliance and enforcement activities, including those related to food misrepresentation. We do this as part of our commitment to openness and transparency, as well as to deter non-compliance.

We also publish reports of Administrative Monetary Penalties (AMPs). In 2023 to 2024, we issued 44 AMPs valued at $196,800 for violations under the Safe Food for Canadians Act or its regulations. This included some related to food misrepresentation. It's important to note that certain enforcement actions (such as AMPs and prosecutions) often span several years before an ultimate resolution.

Enforcement actions

In the 2023 to 2024 fiscal year, we prevented a significant amount of misrepresented food from being sold in Canada. These foods were either removed from Canada, voluntarily destroyed or relabelled before sale.

- 8,050 kg of misrepresented fish

- 10,027 kg of adulterated honey

- 37,300 L of adulterated olive oil

- 1,059 L of adulterated other expensive oil

- 141 kg of adulterated grated hard cheese

- 384 L of adulterated fruit juice

We also took the following actions:

- we issued 23 letters of non-compliance

- we issued inspection reports, including requests for corrective action and following up on non-compliant sample results to determine where the misrepresentation occurred in the supply chain

- we continue to follow up on cases of non-compliance where necessary

- one fish product was voluntarily recalled for an undeclared allergen (egg)

- one situation is being assessed to determine whether more stringent enforcement actions will be considered, such as laying charges for offences under the legislation.

Prosecutions: charges and convictions

In July 2023, we laid charges against 2 companies for offences under the Safe Food for Canadians Act and the Safe Food for Canadians Regulations, including charges related to food misrepresentation:

Next steps

Results of the sampling and testing outlined in this report will inform future work to prevent, detect and deter food fraud. Work will include:

- improved risk-based program design

- surveillance activities

- compliance promotion

- enhanced enforcement

We take food fraud seriously. and encourages anyone who suspects food fraud, or has concerns that a product may be labelled in a misleading manner, to report these to the CFIA through our food compliant or concern web page.

Misrepresentation can occur in various forms across a wide range of foods. Combatting food fraud in Canada is a shared role of government, industry and consumers. The 2024 to 2025 CFIA Departmental Plan outlines our plan for fighting food fraud in the year following this report. We will also continue to monitor emerging information and improve our oversight.