Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Developing your Biosecurity Plan

- 3 Risk Management Practices

- 4 Glossary

- 5 Acknowledgements

- Appendix 1: Allied Programs and Resources

- Appendix 2: Government and Industry Resources for the Sheep Sector

- Appendix 3: Sheep Literature Search Results

1 Introduction

The National Sheep Producer Biosecurity Planning Guide (the Guide) is a tool for use by sheep producers in Canada when you are developing biosecurity plans for your farms. It has been prepared together with the National Sheep On-Farm Biosecurity Standard (the Standard), which contains an explanation of the common approach recommended to sheep producers for implementing biosecurity in the Canadian industry.

The Guide is not meant to be read as a book. Rather, it contains materials and information that you can work with in sections, and as you have time available. It provides an approach to preparing and documenting a biosecurity plan. Some producers will use the Guide to put together their first biosecurity plan; others will use it to test, update and/or modify their current plans.

The Standard and the Guide are intended to work together with your own animal records and on-farm flock health plans, and with the Canadian Sheep Federation's Food Safe Farm Practices Program, animal welfare programs and regulations, industry disease management programs, environmental farm plans, and traceability initiatives that you may already follow. In fact, some of the content in the Standard and the Guide may be duplicated in these programs and initiatives. This has been done to ensure that they are all complete, as stand-alone resources.

1.1 What is Biosecurity and Why is it Important?

Farm-level biosecurity is about a series of management practices designed to minimize, prevent or control:

- The introduction of infectious pathogens onto a farm;

- Spread within a farm production operation

- Export of these pathogens beyond the farm that may have an adverse effect on the economy, environment and human health.

Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA)

Biosecurity practices work together with flock health and disease management programs to reduce the risk of disease transmission and to manage the impact of diseases in sheep flocks. In the National Sheep Producer Biosecurity Planning Guide (The Guide), biosecurity is a proactive component – working to reduce the risk of diseases entering the farm, being transmitted between sheep in the flock and being spread to other farms.

Biosecurity reduces the risk of endemic, economically-significant, production-limiting diseases. Such diseases may be present in many sheep flocks. Clearly, not all endemic diseases are present in every flock, and producers, when developing a biosecurity plan, need to determine which diseases are present or may be potentially at risk to target them in their plans. These target diseases are referred to in the Guide as each farm's diseases of concern.

Biosecurity practices also reduce the risk of transmission of foreign animal diseases (FAD) and newly-emerging diseases. They do so by addressing many of the common modes of transmission and by essentially reducing the survival and transmission of these pathogens.

Biosecurity practices are also important in reducing the risk to producers, their families and their workers of exposure to zoonotic diseases. Zoonotic diseases can be transmitted from sheep to humans, some, like Q fever, with very serious consequences, and from humans to sheep.

Biosecurity helps to reduce the risk of diseases reaching a flock and being transmitted within it. In doing so, biosecurity practices reduce suffering and in some cases mortality, and provide a foundation for improved production.

From this point forward in the Guide, materials will be presented that will help producers develop or improve their farm's biosecurity plan. In several sections additional spaces are included so that producers can enter information about their own flocks, their specific concerns and some analysis of their current practices.

1.2 Biosecurity Objectives for Sheep Producers

- Check Increased awareness and education about disease risk specific to sheep, including foreign animal diseases (FAD), production-limiting diseases and new and emerging diseases.

- Check Increased knowledge about disease prevention, management, and control and using it to develop a farm-specific flock health plan.

- Check Increased productivity per unit; a healthier national flock with lower death loss, better feed conversion and gain, and reduced disease.

- Check Consistent practice of biosecurity standards across Canada; producers, employees, veterinarians, service providers, public agencies, visitors, and their tools, equipment and vehicles present a reduced risk of transmitting diseases between and on farms.

- Check Decreased risk of the transmission of zoonotic diseases.

- Check Awareness that different levels of biosecurity and different biosecurity practices apply to different activities, both on the farm and off; including attendance at livestock exhibits and shows; and that farm gate sales will continue to be undertaken.

1.3 Top Ten Biosecurity Risks for Sheep Farms

Ten common risks were identified for sheep farms in Canada and are listed in the table below. You are encouraged to think about each of them in the context of your diseases of concern, your farm production practices, and your farm layout and facilities. Then, decide whether each is of Low, Moderate or High importance on your farm. Enter the L-M-H designation in the column to the right, with a brief note of explanation, if required. At the bottom of the table, insert any other biosecurity risks that you consider important on your farm

|

Description of Risk | Importance on Your Farm: Low, Moderate, High and Comments |

|---|---|

|

1. Unknown disease risk in sourcing new or replacement stock. |

|

|

2. Sheep leaving the farm, having direct or indirect contact with other animals and returning to the home flock. |

|

|

3. Risk of disease transmission in movement and disposal of deadstock. |

|

|

4. Risk of transmission of disease within your flock; management of diseased animals. |

|

|

5. Access to your flock by people from off-farm (service providers, farm workers and visitors) and risk of transmission of diseases through them from other locations. |

|

|

6. Animal flow through your facility and risk of disease transmission between animal groups within your farm. |

|

|

7. Risk of disease transmission within your flock from manure in your facilities and in storage on your farm. |

|

|

8. Farm facilities, and equipment, tools and vehicles used on your farm that may be contaminated with pathogens. |

|

|

9. Disease awareness among farm workers and their ability to identify potentially at-risk animals. |

|

|

10. Risk of disease transmission from other livestock, working animals, wildlife, vermin, dogs and cats. |

|

|

Additional risks on my farm: |

|

These top ten risks for the industry have been identified during the development of the Guide. Keep them and any additional risks that you have entered above in mind as you proceed to develop a detailed plan for your farm in the following sections.

2 Developing your Biosecurity Plan

Securing a farm is about knowing the risks of disease transmission and the ways in which animals can be exposed to disease, and taking steps to minimize those risks. Prevention through biosecurity is the most cost-effective protection from animal diseases. Building or updating your biosecurity plan will involve reviewing your current practices, farm layout and facilities to identify where gaps in your disease prevention might occur in order to adopt practices that will reduce those risks.

The information provided in the following sections is broken down into 4 main categories, referred to as Principles:

- 1. Animal Health Management Practices

- activities that are directly related to your sheep and how they are handled, including health practices.

- 2. Record Keeping

- information that needs to be recorded, reviewed and used so that your biosecurity plan can be integrated into your farm management practices.

- 3. Farm, Facilities and Equipment

- activities that are directly related to your farm layout, buildings, pens and storage areas, and the tools and equipment you use on farm.

- 4. People

- activities that are directly related to your family, farm workers, service providers and visitors of all kinds.

You will find that these Principles are used to categorize the practices and resource materials throughout the Guide, and will be used to help you work your way through the preparation of a plan.

In Section 2.3 of the Guide you will find a set of checklists, one for each Principle that you can use to assess your current biosecurity practices and identify any gaps you might have. The Guide also contains resource materials that will help you make decisions about what to include in your plan and how to carry it out.

When you are ready to review your current biosecurity plan, or to begin developing a plan for your sheep operation, use the following steps:

- Choose a Principle

- Fill out the self assessment checklist for that Principle

- If any topics or practices are new to you or if you need information, refer to the section(s) identified in the checklist

- Identify possible gaps in your biosecurity practices

- Develop a biosecurity plan for that Principle by preparing protocols for each of the risk management practices you select for your plan. Risk management practices are listed for each Principle in Sections 3 to 6.

As a plan section is prepared for each Principle, repeat the cycle until all four Principles have been reviewed and a full plan is prepared.

Producers who have an ongoing relationship with a flock veterinarian are encouraged to work together with him/her in developing a biosecurity plan. Additionally, other specialists and advisers may be useful; a list of such resources is provided in Appendix 2.

2.1 Diseases of Concern

The first step in preparing a biosecurity plan is to identify and understand the diseases of concern for your farm. Knowing and understanding the diseases of concern for your farm and assessing where the risks of disease transmission are likely to be will help you decide which biosecurity practices to include in your plan and determine the results you should expect.

When identifying diseases of concern for your farm, it will help to become familiar with the diseases that are prevalent in the sheep industry in Canada and in your region.

Diseases that might be a concern on sheep farms in Canada are included in the following table. Enter in the column to the right whether each is of Low, Moderate or High importance on your farm. The table is not intended to list all diseases of sheep; rather it includes those that could have a sizable impact on a sheep farm, and those that could occur in Canada. You are encouraged to read through the list and learn about any you may not be familiar with. Then you can indicate your level of concern about managing the disease or keeping it off your farm in the column on the right side of the chart. Also, there is room at the bottom of the chart for you to add diseases that are not listed in the chart and that you are concerned about. These entries will be useful as you consider adding risk management practices to your biosecurity plan that are targeted on the diseases of concern for your operation.

| Disease Category / Name | Zoonotic (Yes(Y) / No(N)) | Other Susceptible Species | Sources of infection to sheep | Your need to exclude/manage (L-M-H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Campylobacter jejuni & C. fetus fetus |

Y |

Birds |

Manure, feces, birth products, carrion birds, contaminated lambing grounds. Shed in feces of carrier ewes. |

|

|

Chlamydophila abortus (formerly Chlamydia psittaci) |

Y |

Goats, llamas, alpacas |

Birth products; contaminated pasture, bedding; sexual transmission from ram; carrier ewes. Invades through mucous membranes (mouth, eyes, genital) and causes abortion at next pregnancy. |

|

|

Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) |

Y |

All animals; goats, cattle, cats, dogs |

Birth products and fluids and feces; can be spread as an aerosol either from lambing ewes or dried bedding / manure. Also shed in milk. |

|

|

Toxoplasma gondii (Toxoplasmosis) |

Y |

Goats |

Oocysts (eggs) shed in the feces of cats (usually kittens) from eating infected mice or sheep placenta. Cat feces contaminate feed (grain, forage) and pasture. Mice serve as a reservoir of infection for the cats. Mice eat infected placenta. |

|

|

Border Disease (Hairy Shakers) |

N |

Cattle, goats |

The virus is very similar to Bovine Virus Diarrhoea virus (BVDV). Persistently infected (PI) sheep or cattle shed the virus in feces, urine, and saliva contaminating the environment and infect naïve pregnant ewes causing abortion or birth of PI lambs. |

| Disease Category / Name | Zoonotic (Yes(Y) / No(N)) | Other Susceptible Species | Sources of infection to sheep | Your need to exclude/manage (L-M-H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Neonatal diarrhea (rota/ coronavirus, enteropathogenic E coli) |

N |

Kids, calves, crias |

Shed in feces of sheep but build up in environment until the infectious load in lamb rearing area is high enough to cause significant disease in lambs < 2 weeks of age. |

|

|

Neonatal diarrhea caused by Cryptosporidia |

Y |

Kids, calves, crias |

The oocysts (eggs) of this protozoal parasite are shed in the feces and contaminate the lambing, and lamb rearing environment. If a sufficient load, cause disease in lambs 2 days to 6 weeks of age. The oocysts are very long-lived. |

|

|

Pulpy Kidney / Enterotoxemia (Clostridium perfringens type D) |

N |

Goats |

The bacterial spores are shed in feces and contaminate the ground and feed. If the animal lacks immunity and the feed source is rich (lush pasture, heavy grain), the ingested spores will grow in the gut producing a toxin which rapidly kills the lamb (sudden death in otherwise healthy lambs). The spores are very long-lived. |

|

|

Coccidiosis (Eimeria ovinoidalis, Eimeria crandallis) |

N |

None |

The oocysts (eggs) shed in the feces of infected lambs and recovered adults will build up in the environment (barn, drylot, pasture) until load is high enough to cause disease in lambs 3 weeks to 6 months of age. Fecal contamination of feed is associated with more severe levels of disease. The oocysts are very long-lived. |

|

|

Pneumonia |

N |

Goats |

These bacteria normally inhabit the throat of healthy sheep (Mannheimia haemolytica, Mycoplasma ovipneumonia). Environmental stresses (crowding, ammonia from wet bedding, temperature fluctuations, humidity, mixing of groups, etc), will allow severe disease to occur. |

|

|

Orf / Soremouth / Contagious Ecthyma (parapox virus) |

Y |

Goats, llamas, alpacas |

The virus lives in scabs which drop off and contaminate the pens, feeders, wool. The virus can live for months to years in a dry environment. Some animals remain chronically infected (e.g. polls of rams) and serve as reservoirs of infection. |

|

|

Salmonellosis |

Y |

All animals |

Rodent and bird feces contaminate feed. Diarrhea from infected animals contaminate environment. |

|

|

Gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) parasites |

N |

Goats, llamas, alpacas |

(Haemonchus, Teladorsagia, Trichostrongylus, Nematodirus). Eggs passed in feces of infected animals contaminate grazing pastures. Introduced animals can bring in new infections and anthelmintic resistant parasites. |

|

|

Anthelmintic resistant (AR) GIN parasites |

N |

Goats, llamas, alpacas |

Failure to kill GIN parasites after deworming due to the parasite's resistance to that dewormer is an emerging problem. Inappropriate deworming practices can cause this resistance. AR tends to develop more rapidly in goats making their presence a particular risk. New introductions are also a risk for bringing AR parasites onto a farm. |

| Disease Category / Name | Zoonotic (Yes(Y) / No(N)) | Other Susceptible Species | Sources of infection to sheep | Your need to exclude/manage (L-M-H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Johne's disease (paratuberculosis) (Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis) |

Unknown |

Goats, cattle, deer, llamas, alpacas |

Bacteria shed in feces, colostrum, and milk infect lambs when ingested. Bacteria are long-lived and contaminate the environment, including the teats of nursing ewes. Shedding animals may not have symptoms of disease for several years. Also is transmitted from dam to the lamb while in the womb. |

|

|

Scrapie |

N |

Goats |

Infected ewes will shed in birth fluids and placenta at lambing if offspring is genetically susceptible. The prions contaminate the lambing grounds and infect other susceptible lambs and sheep. Also shed in milk and urine. Prions are very persistent in the environment. |

|

|

Caseous lymphadenitis; CL;CLA (Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis) |

N |

Goats, llamas, alpacas |

The bacteria from abscesses can survive for days (water), weeks (feed) to months (soil, feeders, shearing equipment). It invades through skin, and cuts in the oral cavity. The bacteria come from broken abscesses and from the lungs when abscess material is coughed up - contaminating pasture and feed. |

|

|

Maedi visna (Ovine Progressive Pneumonia) |

N |

Goats |

The virus is shed in respiratory secretions which can be aerosolized, and in colostrum, and milk. The virus infects sheep of any age through the mucous membranes (respiratory tract, digestive tract, conjunctiva, semen and in the womb). |

| Disease Category / Name | Zoonotic (Yes(Y) / No(N)) | Other Susceptible Species | Sources of infection to sheep | Your need to exclude/manage (L-M-H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Foot scald |

N |

Goats |

The bacteria (Fusobacterium necrophorum) are ubiquitous in the environment. Dirty, wet, traumatic conditions (wet, muddy pasture, yards or pens) will cause invasion of the soft tissues between the toes with this bacteria. |

|

|

Footrot |

N |

Goats |

The bacteria (Dichelobacter nodosus) cannot live off the sheep's foot for more than a week but infected sheep contaminate pastures. Grazing sheep become infected when the bacteria are present and conditions are wet or dirty. Sheep can be carriers and may be lame or appear normal. |

| Disease Category / Name | Zoonotic (Yes(Y) / No(N)) | Other Susceptible Species | Sources of infection to sheep | Your need to exclude/manage (L-M-H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Listeriosis (Listeria monocytogenes) |

Y |

Goats, cattle |

Fecal-oral through silage and other feeds. The bacteria is shed in manure and found in rodents. It grows well in cool conditions in fecal contaminated wet feed at normal to high pH conditions. Also causes abortion and pink eye. |

|

|

Rabies |

Y |

All domestic mammals. Fox, skunks, bats |

Usually wildlife contact-most commonly fox and skunks. Unvaccinated farm cats and dogs pose a particular risk because of close contact with livestock and humans. |

|

|

Tetanus (lockjaw) |

Y |

All animals |

The spores can live for decades in the soil. An animal with a wound or kidding injury has the wound contaminated with spore containing soil. The bacteria grow in the wound and produce a toxin which is absorbed by the nerves. |

|

|

Deer meningeal worm (Paralaphostrongylus tenuis) |

N |

Goats, llamas, alpacas |

A parasite whose host is the deer and which cycles through land snails and slugs. Sheep become infected by inadvertently eating the infected snails and slugs. The parasite invades the central nervous system causing disease. |

| Disease Category / Name | Zoonotic (Yes(Y) / No(N)) | Other Susceptible Species | Sources of infection to sheep | Your need to exclude/manage (L-M-H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pink eye (Mycoplasma conjunctivae & Chlamydophila pecorum) |

N |

Goats, not cattle |

Sheep can be carriers of the bacteria, shed then in the lacrimal secretions so that when groups are mixed or new animals are introduced, outbreaks occur. |

|

|

Chorioptic mange (Chorioptes bovis) |

N |

Goats, cattle, llamas, alpacas |

Causes dermatitis usually on the pasterns and fetlocks but most importantly on the scrotum of rams-where the inflammation can cause sub-fertility. Transmission is by direct contact between animals and contaminated tools, equipment and bedding. |

|

|

Biting and Sucking Lice |

N |

None |

Nits (eggs) and lice are transmitted by direct contact between animals, contaminated tools, shearing equipment and bedding. |

|

|

Keds |

N |

None |

Ked eggs, pupae and adults are transmitted by direct contact between animals, contaminated tools, equipment and bedding. |

|

|

Ringworm (Club Lamb Fungus) |

Y |

Goats, cattle |

The fungus prefers dark moist conditions and is easily transmitted by direct contact, grooming tools and equipment, shared pens at shows. The spores are very long-lived. |

|

|

Fly-Strike |

Y |

All animals |

The green-bottle fly (Lucilia seracata) is attracted to decaying material and will lay its eggs on live animals that are wet or dirty. Animals with diarrhea, wounds, foot rot, long tails or wool are very susceptible to maggot infestation which causes illness and death. Poor management of deadstock may attract more flies. |

| Disease Category / Name | Zoonotic (Yes(Y) / No(N)) | Other Susceptible Species | Sources of infection to sheep | Your need to exclude/manage (L-M-H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Staphylococcus mastitis (Staphylococcus aureus) |

Y |

All animals |

The bacteria are commonly present in skin infections (including people). Can be transmitted through milking, lambs nursing, teat wounds, dirty hands, poor udder preparation for milk, lack of teat dipping. |

| Disease Category / Name | Zoonotic (Yes(Y) / No(N)) | Other Susceptible Species | Sources of infection to sheep | Your need to exclude/manage (L-M-H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cysticercus ovis (sheep measles) |

N |

Goats |

C. ovis is the intermediate stage of the dog tapeworm, Taenia ovis. The dog, or wild canid becomes infected from scavenging sheep carcasses or being fed uncooked sheep meat. The tapeworm eggs shed by the dog contaminate feed and pasture. The intermediate stage cysts are found in the meat of the sheep and cause carcass condemnation. |

|

|

Fascioloides magna (deer fluke) |

N |

Wild deer in Manitoba and NW Ontario |

This fluke has its adult stage in deer, and its intermediate (larval) stage in snails. The larval are inadvertently grazed by sheep-not the parasite's normal host. The adult fluke is very large and migrates through the liver, damaging blood vessels and causing the sheep to bleed to death internally. No eggs are passed by the sheep in the manure. |

Some of the diseases listed in the chart are the subject of industry programs that may provide information and services to help with managing them. At the time of preparation of the Standard and the Guide, these include a national Voluntary Scrapie Flock Certification Program and a voluntary program to address maedi-visna in Ontario and Québec, Canadian Sheep and Lamb Food Safe Farm Practices Program and various flock health programs including the Western Canadian Flock Health Program in Saskatchewan and Alberta and the Ontario Sheep Health Program in Ontario. Contact your provincial sheep organization for these and other initiatives that may be underway or planned in your area.

2.2 Risk Assessment

Clearly identifying the risks specific to your sheep farm is a critical step in determining what biosecurity practices need to be included in the farm plan. Self-assessment checklists are provided in the following section, and can be used to ensure that all potential risks are considered on your farm.

In practice, identifying specific risks on your sheep farm combines the knowledge of how diseases of concern are transmitted from one animal to another or from fomites to sheep, and documenting all of the transmission points on your farm:

- Some diseases move by direct contact between animals, by physical contact and aerosol spread, and others are transmitted during breeding activities.

- Some move by contact with feces, urine or other excretions/secretions, and can be transmitted by direct contact with these substances, or by indirect contact with contaminated equipment and tools or consumption of contaminated feed, water, bedding or other shared material.

2.3 Self-Assessment Checklists

Checklists are provided below for each of the four biosecurity Principles, and each is followed by a chart for you to record your thoughts about any gaps or improvements that you might have discovered in filling out the checklist. To use a checklist, place a check mark or a brief comment in one of the boxes to the right of each statement, and when you have completed the chart, review your responses to identify areas that are being handled well under your current practices, or topics that might require additional attention. The Section References column identifies the sub-section of the Guide in which you will find information and resource material about each practice.

2.3.1 Animal Health Management Practices

| Biosecurity practices for animal health management | Always/ frequently | Some- times | Never | N/A | Section References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The sheep needed to maintain and grow my flock are produced on my farm. |

3.1.2 |

||||

|

Artificial insemination is used to replace sheep and rams. |

3.1.2 |

||||

|

Embryo transfer is used to replace sheep and rams. |

3.1.2 |

||||

|

I purchase new sheep from a limited number of sources. |

3.1.2 |

||||

|

When I purchase new sheep, I know the health status of the individual animals and of the source flock. |

3.1.2 |

||||

|

My sheep purchases are supported by documentation on the health and disease status of the animals. |

3.1.2; 3.2.1 |

||||

|

When my sheep participate at a show or a fair, I take measures to reduce the risk of disease transmission from other sheep. |

3.1.3; 3.3.2 |

||||

|

When my sheep use common or community pastures I follow specific biosecurity protocols. |

3.1.3 |

||||

|

I avoid commingling my animals with animals from other farms during transportation. |

3.1.2; 3.1.3; 3.1.5; 3.3.5 |

||||

|

All newly-acquired sheep that are brought to my farm are isolated for a period of time determined by the specific diseases of concern for my farm. |

3.1.1; 3.1.2; 3.3.1.; 3.3.2; 3.3.3 |

||||

|

All sheep that return to my farm (e.g. after going to a show, and loaned sheep or rams) are isolated for a period of time determined by the specific diseases of concern for my farm. |

3.1.1; 3.1.3; 3.3.1; 3.3.2; 3.3.3; 3.3.6 |

||||

|

I have an isolation area. |

3.1.2; 3.1.3; 3.1.4; 3.3.1; 3.3.3; 3.3.6 |

||||

|

Sheep in an isolation area are monitored daily for signs of illness. |

3.1.1; 3.1.4; 3.3.1; 3.3.3 |

||||

|

Sheep in an isolation area do not have direct contact or indirect contact (feed, water, shared equipment) with my main flock. |

3.1.4; 3.3.1; 3.3.3 |

||||

|

Sheep in an isolation area are enclosed and sheltered and do not share common airspace with my main flock. |

3.1.4; 3.3.1; 3.3.3 |

||||

|

The equipment used for treatment, handling and other husbandry chores in the isolation area is only used for that purpose. |

3.1.4; 3.3.1; 3.3.4; 3.3.6; 3.3.8; 3.3.9; 3.3.10 |

||||

|

When the equipment used for treatment, handling and other husbandry chores in the isolation area is used for the main flock, the equipment is cleaned and disinfected between uses. |

3.1.4; 3.3.2; 3.3.3; 3.3.4; 3.3.6; 3.3.8; 3.3.9; 3.3.10 |

||||

|

Dedicated clothing and footwear are used when working with sheep in the isolation area. |

3.1.4; 3.3.1; 3.3.8 |

||||

|

My employees work with the main flock before handling sheep in the isolation area(s). |

3.1.4; 3.3.3 |

||||

|

I have a protocol in effect for releasing sheep from isolation. (Note: such a protocol may include testing, vaccinating or treating for diseases of concern.) |

3.1.1; 3.1.4; 3.1.7; 3.3.1 |

||||

|

More susceptible animals in the flock are separated from older and/or diseased animals. |

3.1.5; 3.3.3 |

||||

|

Separation of animals by susceptibility applies to sheep movement through the farm, handling order, and worker contact with the animals. |

3.1.6; 3.3.3 |

||||

|

I use a flock health program to manage disease on my farm. |

3.1.1; 3.2.3 |

||||

|

My flock health program includes written protocols for disease control measures (e.g. vaccination, parasite control, disease testing, biosecurity) to be followed during specific production activities. |

3.1.1; 3.1.7; 3.2.3 |

||||

|

I use written treatment protocols for the management of sick animals. |

3.1.1; 3.2.1 |

||||

|

I follow written protocols for the use of all prescribed drugs, including withdrawal times. |

3.1.1; 3.2.1 |

||||

|

I routinely inspect and maintain my facilities to avoid pest and predator invasion. |

3.1.8 |

||||

|

Pest and insect management is in place. |

3.1.8 |

||||

|

I follow a protocol to prevent contact between wildlife and my sheep. |

3.1.8 |

||||

|

I follow a health plan for the dogs on the farm (working, guardian and pet) that includes vaccination against rabies and treatment for tapeworms. |

3.1.8; 3.1.9 |

||||

|

Female cats are spayed to reduce the risk of toxoplasmosis |

3.1.8 |

Based on the self evaluation:

- What animal health management gaps have I identified on my farm?

- What steps can I take to correct these gaps?

2.3.2 Record Keeping

| Biosecurity practices for record keeping | Always / frequently | Some-times | Never | N/A | Section Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

I maintain farm records for my sheep operation that include health records for each individual animal in the flock. |

3.1.1; 3.2.1 |

||||

|

My farm records include production records for each sheep including reasons for death or culling. |

3.2.1 |

||||

|

My farm records include production records for the flock overall. |

3.2.1 |

||||

|

My farm records include all disease occurrences and their treatment. |

3.1.1; 3.2.1 |

||||

|

My farm records include a record of prophylactic treatments (e.g. deworming) and vaccinations. |

3.1.1; 3.2.1 |

||||

|

My farm records include a record of mortalities, necropsies and any laboratory results. |

3.1.1; 3.2.1; 3.3.10 |

||||

|

Biosecurity training of farm workers is maintained in employee or farm records. |

3.2.2 |

||||

|

My farm records can be used to provide health and disease records for individual animals and for the flock to potential purchasers of live sheep. |

3.2.1 |

||||

|

I maintain an emergency response plan for use in case of a disease outbreak on the farm or in the area. |

3.2.3; 3.3.1 |

Based on the self evaluation:

- What record-keeping gaps have I identified on my farm?

- What steps can I take to correct these gaps?

2.3.3 Farm, Facilities and Equipment

| Biosecurity practices for farm, facilities and equipment | Always / frequently | Some-times | Never | N/A | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

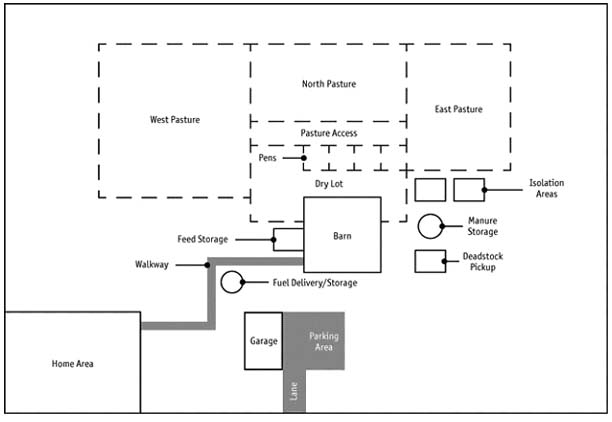

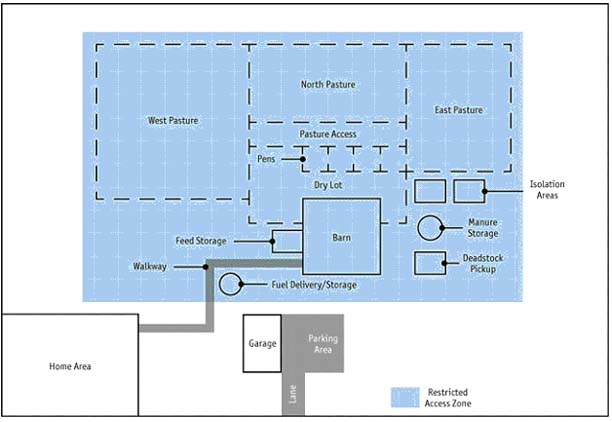

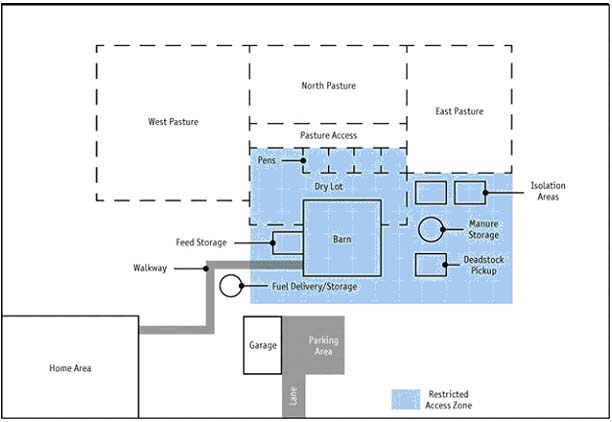

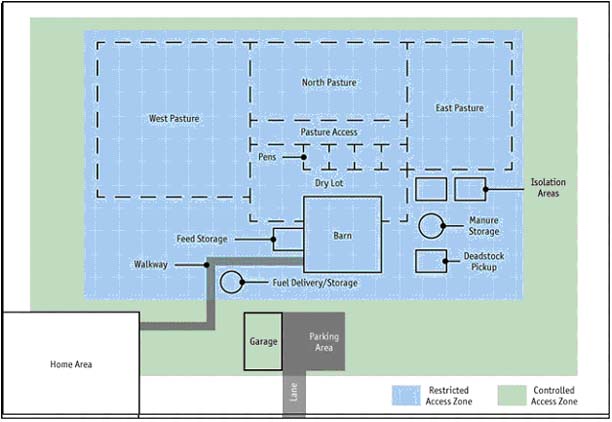

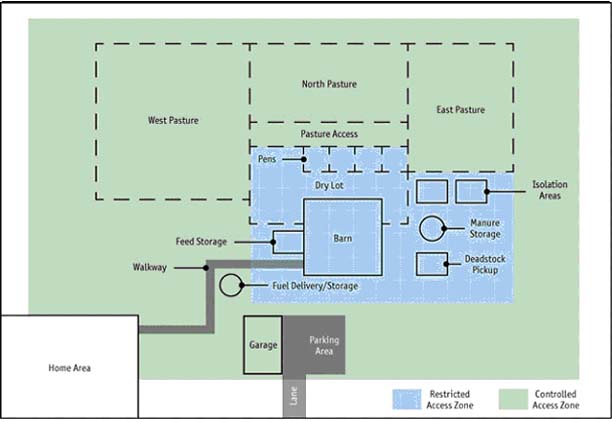

I have a map or diagram of my farm that shows facilities, working areas, pastures and pathways. |

3.3.1 |

||||

|

Biosecurity zones on my farm are identified. |

3.3.1; 3.3.5 |

||||

|

I use signs at access control points to describe my biosecurity protocols. |

3.3.1; 3.3.5 |

||||

|

I provide a dedicated parking area for farm workers and visitors that is separate from animal management and housing areas. |

3.3.1; 3.3.5; 3.4.3 |

||||

|

I have perimeter fencing around my sheep operation. |

3.1.5; 3.3.1 |

||||

|

My farm has specified practices for cleaning and disinfection. |

3.3.2; 3.3.5 |

||||

|

My farm workers are familiar with the cleaning and disinfection processes on my farm. |

3.2.2; 3.3.2; 3.3.4; 3.3.5 |

||||

|

Perimeter and interior fencing on my farm is inspected and maintained |

3.1.5; |

||||

|

Pens and other livestock areas on my farm are cleaned and disinfected when risk events (e.g. abortion outbreak) occur. |

3.1.1; 3.3.2; 3.3.3 |

||||

|

Specified risk areas on my farm (e.g. isolation areas for newly-introduced or sick sheep, etc.) are cleaned and disinfected after each use. |

3.3.1; 3.3.2; 3.3.3 |

||||

|

Barn facilities and pens on my farm are designed and laid out to facilitate good biosecurity practices. |

3.3.1; 3.3.3 |

||||

|

I provide dedicated equipment and tools for use in specific risk areas, such as the isolation area. |

3.3.4; 3.3.6; 3.3.8 |

||||

|

My equipment and tools are cleaned and disinfected between uses. |

3.3.2; 3.3.4; 3.3.6; 3.3.8; 3.3.9; 3.3.10 |

||||

|

Equipment and tools on my farm are identified for dedicated use (eg manure movement, feed handling). |

3.3.3; 3.3.4; 3.3.6; 3.3.7; 3.3.8; 3.3.9; 3.3.10 |

||||

|

Feeders and feeding areas are kept clean of manure, old feed and other contaminants. |

3.3.2; 3.3.4; 3.3.7 |

||||

|

Water bowls and water troughs are cleaned regularly. |

3.3.2; 3.3.4; 3.3.7 |

||||

|

Equipment used to move and handle deadstock is cleaned and disinfected immediately after each use. |

3.3.2; 3.3.4; 3.3.10 |

||||

|

Vehicles from my farm are used to transport sheep to and from the farm. |

3.1.2; 3.1.3; 3.3.5 |

||||

|

Livestock transportation vehicles are cleaned between uses. |

3.1.2; 3.1.3; 3.3.2; 3.3.5 |

||||

|

Sheep movement pathways on my farm are cleaned immediately following use by higher-risk sheep. |

3.1.6; 3.3.1; 3.3.2; 3.3.3; 3.3.- |

||||

|

Manure is removed regularly and stored securely. |

3.3.6 |

||||

|

I keep samples of feed batches for testing and tracking purposes. |

3.3.7 |

||||

|

I store feed in a location that is secure from access by pests and animals. |

3.3.1; 3.3.7 |

||||

|

I provide quality water and test it at least annually for its safety for livestock. |

3.3.7 |

||||

|

Clean bedding is stored in a manner that keeps it free from contamination from animal products (e.g. feces). |

3.3.7 |

||||

|

Soiled bedding is removed regularly and disposed of away from the flock. |

3.3.7 |

||||

|

Shearing protocols are followed on my farm that include sequence, cleanliness and care of nicks and abrasions. |

3.3.8 |

||||

|

Needles and scalpels are only used once and then discarded into a suitable container. |

3.3.9 |

||||

|

Deadstock is immediately removed and stored in an area away from the flock, facilities, food and water, and secure from scavengers, dogs, cats and pests. |

3.1.8; 3.3.1; 3.3.7; 3.3.10 |

Based on the self evaluation:

- What farm, facilities and equipment gaps have I identified on my farm?

- What steps can I take to correct these gaps?

2.3.4 People

|

Biosecurity practices for people |

Always / frequently |

Some-times |

Never |

N/A |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

My family members and farm workers understand what zoonotic diseases are and understand how to protect themselves against zoonotic disease risks. |

3.2.2; 3.3.2; 3.4.4; 3.4.5 |

||||

|

I hold regular biosecurity education sessions and on-the-job training with my farm workers. |

3.2.2; 3.2.3; 3.3.1; 3.3.2; 3.3.3; 3.3.4; 3.3.5; 3.3.6; 3.3.7; 3.3.8; 3.3.9; 3.3.10; 3.4.4 |

||||

|

All farm workers on my sheep farm understand the biosecurity practices that apply to their work. |

3.2.3; 3.3.2; 3.3.4; 3.3.5; 3.3.6; 3.3.7; 3.3.8; 3.3.9; 3.3.10; 3.4.3; 3.4.4; 3.4.5 |

||||

|

I plan visits to my farm by service providers and visitors in advance. |

3.3.1; 3.3.2; 3.3.5; 3.3.8; 3.4.1; 3.4.2; 3.4.3 |

||||

|

I do a risk assessment when planning a visit by a service provider or visitor to my farm. |

3.3.1; 3.3.5; 3.3.8; 3.4.1; 3.4.2; 3.4.3 |

||||

|

Service providers and visitors know and understand the biosecurity practices that apply to their activities on my farm. |

3.3.1; 3.3.2; 3.3.4; 3.3.5; 3.3.8; 3.3.10; 3.4.1; 3.4.2; 3.4.3; 3.4.4; 3.4.5 |

||||

|

I have specific practices that are designed to address the risks presented by visitors to my farm that have previously visited a foreign country and may have been in contact with a pathogen. |

3.3.2; 3.4.1; 3.4.2; 3.4.3 |

||||

|

Visitors and service providers on my farm are identified and my farm workers are aware of their presence and the purpose of their visit. |

3.4.3; 3.4.4 |

Based on the self evaluation:

- What people gaps have I identified on my farm?

- What steps can I take to correct these gaps?

3 Risk Management Practices

In the following sections of the Guide, the general risks in each of the four Principles are briefly discussed, followed by a list of risk management practices and resource material to help you prepare a biosecurity plan for your farm. With your checklist information, review the material for each Principle area and select the practices that you wish to include in your plan.

3.1 Principle 1: Animal Health Management Practices

Goal – Minimize the health risk to your flock from sheep and other animals

3.1.1 Strategy 1 – Prepare and use a flock health program

A program that describes the flock health regimens and practices is used for day-to-day flock management. It is the basis for monitoring flock health and is a key source when considering flock performance. A biosecurity plan is integral to and supportive of the flock health program.

Producers should have a Flock Health Program that defines the health goals and practices for their flocks. A flock health program, developed with your flock veterinarian will be a key reference for the diseases of concern for each flock, a description of the vaccination regimen that is in use, and a source for any treatment guidelines. The flock health program will also guide producers in what health records need to be kept for individual animals and for the flock overall (see also Principle 2 – Record Keeping).

A flock health program should include:

- Check Guidelines for flock health monitoring

- Check Staff training guidelines for recognition of diseases and use of the plan

- Check Documentation of diseases of concern for the farm

- Check Vaccination strategy for various age groups on the farm

- Check Vaccination and treatment strategies for animal additions

- Check Vaccination and treatment strategies for animal movements

- Check Disease monitoring/test strategies

- Check Strategies for sheep under treatment

- Check Treatment protocols for diseases of concern on the farm

- Check Euthanasia protocol and guidelines for decision-making

- Check Meat and milk withholding times/strategies

- Check Proper storage and records for vaccines and drugs

- Check Appropriate disposal of empty and out-dated product containers

- Check An annual review of the plan

3.1.2 Strategy 2 – Sourcing sheep

Additions are limited and when necessary animals are sourced from suppliers with flocks of known health status. As few sources as possible are used. New stock is isolated upon arrival.

3.1.2.1 Description

Building a flock, replacing culled or lost sheep, and adding stock to improve the genetics of a flock may require purchasing sheep to be integrated into an existing flock. Feedlots that are regularly selling animals ready for slaughter routinely acquire new animals for feeding, often in large numbers. Currently, information about the health status of acquired animals is often informally provided or not available, and intermediaries, such as truckers and auction markets, often feature commingling, either when they are sourced for sale or in the selling location, that increase risks of disease transmission.

A written protocol for purchasing sheep and lambs, that takes into consideration diseases specific to the farm, will provide some guidance when evaluating these purchases. Different production categories will need different protocols; different considerations exist for breeding stock compared to other animals. Having a list of questions to ask that are specific and relevant to the sourcing route will also help determine risk.

3.1.2.2 Risks

- Purchased sheep may have a disease(s) that will negatively impact their production and/or growth.

- Purchased sheep may have or may be carrying a disease and transmit it directly or indirectly to your flock.

- Purchased sheep may have been vaccinated or treated in a manner that is incompatible with your flock, and either the acquired sheep or your flock become infected.

3.1.2.3 Risk Management Practices

- Minimizing purchases and raising more of your own new and replacement stock will reduce the risk directly. When using artificial insemination practices, work with known, accredited sources for semen and embryos.

- Feedlot operators and other producers buying in lambs as feeders can develop sufficient regular sources and plan ahead rather than purchasing from uncertain sources and sources that feature indiscriminate commingling. If this is not possible, test, treat and isolate; alternatively, manage the collected flock separately from others on the farm, using a modified all-in-all-out production system.

- Plan ahead for additions, adding sheep infrequently and allow advance planning by your chosen suppliers.

- Limit the number of sources you buy from when sourcing new and replacement sheep.

- Buy directly from replacement stock breeders; usually consisting of either maternal-trait animals (usually ewe lambs) and terminal sire-trait animals (usually rams), to ensure more consistent health information about the animals and the source flock and to limit the possibility of commingling.

- Know the animal health practices of all your suppliers and their compatibility with the practices of your home farm.

- Ask all lamb or sheep suppliers to provide health and disease records for all animals they supply and the flock(s) they have come from; a vendor declaration form that is presented when purchases are being considered would be very useful.

- In all cases, ensure that source-flock health programs (specifically, their vaccination and disease status) are compatible with yours. Working with your flock veterinarian and, if possible, with the source-flock veterinarian will be useful in getting this right.

- Additions should be of equal or higher disease-program status, e.g. participation in maedi visna or Scrapie programs.

- Transport purchased animals yourself or use dedicated carriers whose biosecurity practices are known and are suited to your farm practices.

- Prepare protocols for management of new stock on arrival for specific diseases; these might be specific to different types of stock (e.g. breeding stock and others).

- In all cases, test, treat and isolate purchased animals upon arrival at your farm.

- Adopt a specific isolation strategy for each source flock by making a list of undesirable diseases specific to the flock and adopt appropriate procedures for each (for example, the procedure is different for maedi visna versus foot rot). Note, however, that isolation will not be sufficient to fully prevent the introduction of some diseases, including Johne's disease and some causes of infectious abortion.

3.1.3 Strategy 3 – Manage sheep that leave and return to the home farm

If sheep are moved off the farm they have biosecurity practices consistent with their home-farm practices, and upon their return they are treated as newly-sourced animals.

3.1.3.1 Description

Attendance at fairs and shows or loaning rams for breeding purposes are a normal part of the industry for many producers, both for social and business purposes.

Specifically, show performance may be related to success at selling breeding stock. However, this puts your sheep in environments in which biosecurity may not be consistent with or as rigorous as your practices. While your sheep are there, an off-farm location is much like a part of your farm, and your biosecurity practices ideally need to be replicated during the event. People attending the event often have access to and direct contact with the animals being shown, and the biosecurity of common walkways and adjacent pens are often not known. Fairs and shows may have biosecurity protocols, but this is inconsistent and unregulated.

Loaning or borrowing rams for breeding purposes is a convenient way to balance production and improve genetics in a flock. Moving and transferring a ram from one farm to another sheep operation is generally in your control, and therefore can be managed carefully from a biosecurity point of view. While all common/endemic disease risks need to be addressed when sheep are commingled, specific sexually-transmitted diseases such as Chlamydia are also significant risks to both operations from loaning or borrowing rams.

3.1.3.2 Risks

3.1.3.2.1 Shows and Fairs

- Sheep and/or other stock attending the event may have or may be carrying a disease and may transmit it directly or indirectly to your sheep. Examples of transmission risks by direct contact include nose-to-nose, aerosol contact, contact via manure, used bedding, common feeders and waterers, and equipment used at the event location.

- Sheep and/or other stock attending the event may be transported in contaminated vehicles and may introduce pathogens onto the facility.

- Event organizers, judges, etc. may transmit pathogens on their hands, clothing and/or footwear and come into close contact with your sheep.

- People attending the event may transmit pathogens on their hands, clothing and/or footwear and come into close contact with your sheep.

- Facilities and equipment at the event may not have been cleaned from previous uses and/or may not be cleaned and disinfected during the event.

- Loading facilities at the show/fairground may be contaminated with manure and other excretions that contain pathogens.

- The vehicle used to transport your sheep to and/or from the show/fair may not have been cleaned and disinfected before loading your sheep.

- The vehicle used to transport your sheep may be carrying other sheep and livestock that infect your sheep.

- The vehicle used to transport your sheep may not be cleaned and disinfected before arriving at your farm and may deposit contaminated material on your loading dock and/or other areas of the farm.

- Returning sheep may be infected with a disease from contact at the event and transmit it to your flock.

3.1.3.2.2 Rams Loaned or Borrowed for Breeding

- The flock to which the ram is loaned may have or may be carrying a disease and transmits it directly or indirectly to the ram.

- The ewes in the flock to which the ram is loaned may have a sexually-transmitted disease and pass it directly to the ram.

- The flock from which the ram is borrowed may have or may be carrying a disease and the ram transmits it directly or indirectly to the receiving flock.

- The borrowed ram may have a sexually-transmissible disease and may pass it directly to the bred ewes.

- Sheep or other animals at the borrower's farm may have been vaccinated or treated in a manner that is incompatible with the ram's home flock, and may directly or indirectly infect the ram.

- The vehicle used to transport the ram back to his home farm may not have been cleaned and disinfected before loading him, and may serve as a source of infection.

- The vehicle used to transport the ram is carrying other sheep and livestock which infect the ram and/or the home or receiving flock.

- The vehicle used to transport the ram may not be cleaned and disinfected before arriving at the home or destination farm and deposits contaminated material on its loading dock and/or other areas of the farm.

- The returning ram may be infected with a disease from contact at the borrowing farm and transmits it to the home flock.

- The returning ram may be contaminated with infective material and deposits it in the production area(s) of the home farm.

3.1.3.3 Risk Management Practices

3.1.3.3.1 General

- If sheep are moved off the farm, they should be commingled only with sheep and other animals of similar/compatible health status.

- If possible, appropriate biosecurity protocols should be in place anywhere sheep are taken.

- Direct action can be taken, such as providing clean and own-use waterers and other equipment to the site, providing own-use feed, water and bedding, and cleaning and disinfecting pens and holding areas.

- When they are returned to the farm, their re-entry should be managed consistent with Strategy 1 above.

- Animals returning from any off-farm activities are transported either in your own vehicle or in a third-party carrier that has been cleaned and disinfected after the previous use.

- When the returning sheep arrive at your farm, direct the transport vehicle to follow a predetermined route that avoids potential contamination.

- Returning sheep should be placed in isolation for a period of time and should be tested, vaccinated and otherwise treated as determined by your diseases of concern. Note, however, that isolation will not be sufficient to fully mitigate the introduction of some diseases, including Johne's disease and some causes of infectious abortion.

3.1.3.3.2 Shows and Fairs

- Learn about the biosecurity practices of any shows and fairs you are considering, and attend only those that are compatible with your practices. Encourage fair and show organizers to establish biosecurity programs and require all attendees to adhere to them.

- Limit duration at shows and fairs without being late, which could lead to penalties.

- Bring your own feed, bedding (if possible), feeders, waterers and handling equipment to the event and use them exclusively.

- Limit personal contact of sheep; require those that must contact the sheep to wash and sanitize their hands and footwear before entering your pens and before handling your sheep.

- Transport your sheep to these events in your own vehicle or use dedicated carriers whose biosecurity practices are known and are suited to your farm practices.

- Test, treat and isolate your sheep upon their return to your farm, following the protocols developed as described in Section 3.1.4.

3.1.3.3.3 Rams Loaned or Borrowed for Breeding

- Limit loaning or borrowing rams. Learn about the biosecurity practices of the farms you are considering and work only with those that are compatible with your flock biosecurity practices.

- Compare vaccination and treatment regimens with the borrowing or loaning producer to ensure compatibility.

- Transport rams to and from the borrowing farm in your own vehicle or use dedicated carriers whose biosecurity practices are known and are suited to your farm practices.

- Isolate your ram upon its return, following the protocols developed as described in Section 3.1.4.

3.1.4 Strategy 4 – Isolate sick sheep, flock additions and returning sheep

Sheep showing signs of disease are moved into an isolation area away from the healthy flock until the disease has been resolved. Animals brought onto the farm are held in isolation until disease status has been determined or is resolved.

3.1.4.1 Description

Isolating sick sheep or sheep of unknown disease status is very effective in reducing the risk of disease transmission. Direct contact between animals, via aerosols for some diseases and via excretions can be avoided more easily when newly-arrived and returning sheep and sick sheep are isolated from the rest of the flock. An isolation area is available. It is a dedicated pen or enclosure that is separated from movement pathways and other pens and enclosures and ideally has a separate airspace. Ideally, access is also convenient for workers and veterinarians. Handling and management protocols that ensure isolation of the sheep should be followed by workers and others who need to enter the isolation area.

It is important to note that there are limits to the effectiveness of isolation for sheep and that isolation protocols need to be disease-specific. Some diseases of sheep will not display visible clinical signs during limited isolation and are not reliably diagnosed by testing. These include Johne's disease, several reproductively-spread diseases, and several abortion agents. Also, some animals can carry certain diseases without displaying clinical signs, but can still transmit them to other animals; again, the disease may not be revealed during a stay in isolation. For all these reasons, continued observation of isolated sheep is advised following their integration into the flock.

Sheep that are isolated in this manner can be observed and treated individually. Separate records can be kept, and when the isolated sheep are confirmed to be recovered from the disease they were suffering, or tested free of disease of concern, or when vaccination and/or treatment has taken effect, the isolated sheep are (re)integrated with the flock.

3.1.4.2 Risks

- Animals that have been brought to the farm or brought back from a show or fair may transmit a disease to the home flock.

- Diseased animals may transmit the disease they are suffering to their flock-mates.

- Pathogens may be transmitted to the main flock on the hands, clothing and/or footwear of farm workers and others who are required to enter the isolation area(s).

- Visitors may enter the isolation area(s) on purpose or by accident and subsequently transmit pathogens to the rest of the flock.

- Excretions and secretions from diseased sheep and from sheep of unknown disease status in the isolation area may be spread to the main flock area(s) by equipment and tools or by guardian animals, dogs, cats and pests.

- Delay in the removal of deadstock in the isolation area may provide the opportunity for them to be scavenged by guardian animals, dogs, cats and/or predators that may then transmit pathogens to the main flock.

3.1.4.3 Risk Management Practices

3.1.4.3.1 General

- Establish areas that are dedicated to isolation, and consider different isolation areas for newly introduced / returning animals and sick animals. The same area could be used for both purposes only if it is cleaned and disinfected between uses. However, a sick animal and a newly introduced animal should not be isolated in the same area at the same time.

- Isolation areas should have separate air space, and no shared alleyways, feeders, etc.

- The isolation area(s) should be located away from pathways used to move other sheep and animals around the farm, using procedures described in Strategy 5. Separation from other animals on the farm should be provided, including guardian and working animals and dogs and cats. The isolation area(s) should be available to farm workers for both frequent observation and care.

- The isolation area has a specific entrance and exit to avoid contamination of healthy sheep.

- Access by anyone not directly involved in the isolated animals' care should be restricted.

- The isolation area should be cleared of manure and bedding, and cleaned and disinfected before use by other sheep.

- Feed and water used in the isolation area should be removed after each use, and waterers and feed bunks should be cleaned and disinfected (C&D) before use by other sheep, using appropriate materials and C&D methods (see Principle 3).

- Tools and equipment used with diseased or unknown-status sheep should be kept apart from those used with the rest of the flock. Tools and equipment used in the isolation area should not be used in other areas of the farm, or if they must be used elsewhere, they should be cleaned and disinfected before use, using appropriate materials and C&D methods.

- Those working with isolated sheep should use biosecurity practices that are specifically designed for the isolation area.

- Access by guardian animals, dogs, cats and pests should be limited so that they do not spread potentially-infective material elsewhere on the farm.

3.1.4.3.2 Isolating sick sheep

- A list of the protocols you will need should be prepared. Here are some suggestions:

- When to move sick animals to an isolation area (including what observations are required and what diseases are to be considered)

- When a group / pen of sheep is sick, consider keeping that group in place and instituting isolation measures around the group to prevent disease transmission to healthy animals.

- Management of other sheep in the area(s) in which the sick animal has been found, and cleaning and disinfection of that area and of movement pathways

- Testing/vaccinating/treating

- Recording testing, vaccination and treatment information, and observations of the clinical signs

- Determining the isolation period

- Maintaining records of their health and condition during the period of isolation

- Access protocols for workers – when to tend to the isolated sheep (both schedule and sequence); hygiene, clothing and footwear upon entry and exit; tools and equipment (including feeders and waterers)

- Management of manure and bedding

- Timely management of deadstock and culls

- (Re)entry to the main flock (conditions for completion of isolation; method of introduction)

- Avoiding anthelminthic/antimicrobial resistance

- Biosecurity protocols that are designed to address the disease encountered and its treatment regimen, with respect to feed, water, bedding and manure management, and cleaning and disinfection should be used.

- Treatment and all observations should be recorded consistently on a daily basis or more often as required by the severity of the condition being observed/treated.

- Sheep should be (re)introduced to the main flock only when the risk of disease transmission has been managed. If a sheep did not survive, samples should be taken or a necropsy should be done.

- If an animal tests positive for a disease, disposition of the animal should be decided: whether to manage or cull.

3.1.4.3.3 Introducing new stock

- A list of the protocols you will need should be prepared. Here are some suggestions:

- Handling new arrivals and returning sheep from the loading/unloading ramp to the isolation area(s)

- Testing/vaccinating/treating new arrivals and returning sheep upon arrival

- Recording information received about newly-acquired sheep, testing, vaccination and treatment information, and observations of their condition

- Determining the isolation period

- Maintaining records of their health and condition during the period of isolation

- Access protocols for workers – when to tend the isolated sheep (schedule and sequence); hygiene, clothing and footwear upon entry and exit; tools and equipment (including feeders and waterers)

- Management of manure and bedding

- Management of deadstock and culls

- (Re)entry to the main flock (conditions for completion of isolation; method of introduction)

- New stock should be isolated for a period of time that allows for signs of diseases of concern to become evident, for shedding of pathogens to cease or for vaccination and/or treatment to take effect. The appropriate periods for diseases of concern can be discussed with your flock veterinarian.

- Newly (re)introduced sheep and/or commingled animals should be vaccinated, tested and/or treated with consideration for all diseases of concern on your farm.

- All isolated animals should be observed daily or more frequently as appropriate to the condition being observed/treated and all observations should be recorded and reviewed.

3.1.5 Strategy 5 – Manage contact with neighbouring/other livestock

Sheep in the home flock are housed, moved and pastured in such a manner that the risk of contact with neighbouring livestock or other livestock on the farm is addressed.

3.1.5.1 Description

Fenced areas can be designed and put to use to avoid direct contact between pastured sheep and other animals on the farm, and between your flock and animals on adjacent farms. However, most fencing systems will not eliminate contact with all wildlife.

Therefore, alternate strategies are needed to mitigate these risks that are inherent to pastured livestock. The following can be considered:

- Pasture management on the farm: knowing what diseases are common risks among the livestock on a farm (i.e. diseases that can be spread among different livestock – e.g. cattle and sheep), and using both separated pasture areas and scheduling pasturing of sheep and other livestock in the areas to minimize contact;

- A similar approach to pasture management between neighbouring farms: knowing what livestock is likely to be turned out in adjacent fields, knowing their disease status, and cooperating together in scheduling pasture use to avoid high-risk access between animals;

- Use of guardian animalsto defend the flock from wildlife that may be present;

- Knowing the clinical signs of and, where possible, testing for diseases that could be spread to your sheep by wildlife.

3.1.5.2 Risks

- You co-pasture your sheep and cattle. When you turn out a group of sheep onto the pasture after a breeding cycle, they could encounter a cow that you have not noticed is suffering from bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD), and one or more of the sheep could become infected.

- Sheep and other livestock on your farm are housed in different areas of the same barn facility. Due to the layout of the barn, the pathways use by all species lead through some of the sheep pen areas, and pathogens may be transmitted to the sheep from manure deposited in the pathways.

- Your farm has single fence lines around all of your pastures, and sheep are sometimes nose-to-nose with sheep or other livestock in the adjacent farm's pasture. Unbeknown to you, the sheep on the adjacent farm may have an infectious disease, to which your sheep are not immune, and it can be transmitted via direct or aerosol means to members of your flock. Other livestock with a disease to which sheep are also susceptible can represent the same potential risk.

3.1.5.3 Risk Management Practices

3.1.5.3.1 Other livestock on your farm: pastures and housing

- Perform a risk assessment on the specific contact that you anticipate for animals on your farm including common pasture use, movement between farm areas, and housing in close proximity. Include consideration for susceptibility for common diseases among the species you are working with (e.g. Johne's disease, BVD, Border disease, Salmonellosis), and their specific cross-species risks. For example, commingling of sheep and cattle on pasture can be beneficial with respect to internal parasites, but mixing sheep and goats can be a major challenge for disease control (internal parasites, Johne's, caseous lymphadenitis).

- A pasture schedule can be used to enable the outcomes of your risk assessment such that sheep and other livestock on your farm that represent a biosecurity risk to one another are not pastured in common or adjacent fields.

- Pastures and facilities should be connected by pathways that allow movement to and between facilities and pastures with planned/limited interaction with other animals.

- Sheep pastures and other production areas should be observed regularly to identify potentially-infectious material, and should be cleared as soon as it is identified.

- Pasture areas and shelter/containment facilities for your other livestock should be designed and maintained in good condition to limit unintended commingling between sheep and other livestock in and around those facilities.

- Internal fencing and pens can be installed and maintained so that you can keep sheep separate from other livestock on your farm.

3.1.5.3.2 Other farms and adjacent farms

- Pasture management should be discussed with neighbouring producers who have sheep and/or other species with common disease-susceptibility; a schedule for pastures can be agreed that avoids high-risk interaction between your flock and the neighbouring producer's livestock.

- Fencing should be installed and maintained in good repair so that you can limit direct contact between your sheep and sheep or other livestock on adjacent farms.

3.1.6 Strategy 6 – Plan sheep movement through the production unit

Sheep are moved through and within the production unit by pathways that limit their exposure to diseased or potentially infectious animals and materials. Consideration should be given to health status, age and production stage.

3.1.6.1 Description

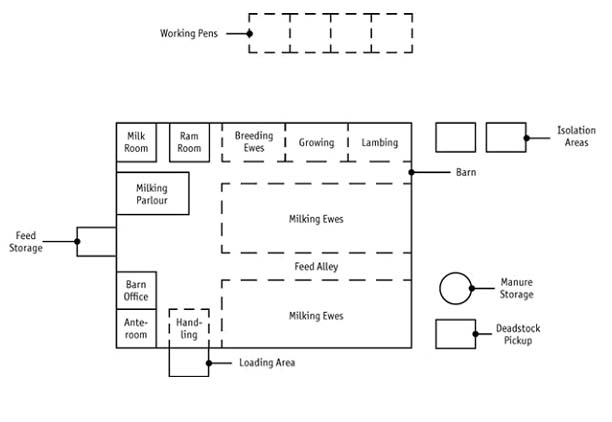

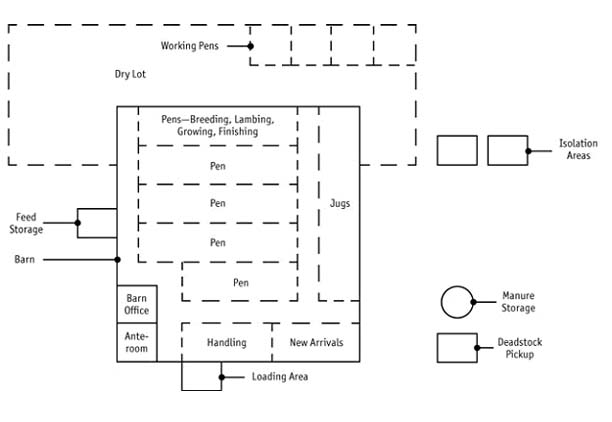

Sheep are moved regularly in the production unit. Dairy operations move milking ewes through the milking unit daily from their pens and back; movement to and from working pens and to and from pasture are less frequent but are similarly planned and managed. Movement to and from the isolation and lambing pens happens on a less frequent basis, but is important since it involves the movement of potentially diseased sheep and more susceptible lambs.

Using the farm maps/diagrams described in Section 3.3.1, decisions can be made about where sheep are potentially at risk when moving and where they represent risk to others; routes can be planned and practices can be put in place to reduce the risks identified. The map or farm diagram will identify where pathways between areas of the farm are used for sheep movement; the diagram of the barn and the main production area will help you identify where pathways run past areas of identified risks.

3.1.6.2 Risks

- Diseased animals may transmit disease directly to sheep that are passing closely by their pens by direct contact or by aerosol means.

- Susceptible sheep may be exposed to pathogens from feces or other excretions deposited in pathways by diseased or more resistant flock-mates.

3.1.6.3 Risk Management Practices

- Using a map of the production area(s) as a guide, study and identify preferred pathways and routes by their relative risks for healthy animals.

- Avoid routes and pathways that take healthy sheep past or adjacent to sick sheep.

- Avoid routes and pathways that take sick sheep past or adjacent to healthy sheep, especially those that are more susceptible.

- Plan movement in the following sequence: from young to older stock, from healthy to diseased and from more to less susceptible sheep, considering the diseases of concern for your farm.

- Review movement plans with farm workers.

3.1.7 Strategy 7 – Implement sheep health protocols for specific situations

Protocols to limit risks of disease transmission are in place for specific production activities, and farm workers understand and employ them.

3.1.7.1 Description

Some of your regular flock management activities may expose them to risks of disease transmission. These activities include lambing, abortion management, milking, disease testing, vaccination and parasite control. By their nature some require grouping of sheep in close quarters, some expose individual sheep to specific disease risk; some involve two or more sheep at different stages of development and therefore of different levels of susceptibility; and some produce by-products that themselves present disease risks.

3.1.7.2 Risks

- Pathogens present in pregnant ewes may be passed to their offspring or to other ewes or lambs during lambing, or may contaminate the lambing site.

- Lambs may not be checked soon enough after lambing and managed early enough for neonatal conditions and the lambs' disease susceptibility is thereby increased.

- Pathogens present in pregnant ewes may be released into the farm environment during abortion and may be transmitted to other animals in the flock directly or via pests, dogs, cats, wildlife or working animals.

- Mastitis severity and spread of contagious mastitis pathogens or exposure to environmental pathogens may be increased by lacking or incorrect udder preparation and care before and after milking.

- Disease testing may be incomplete, leaving some diseased sheep unidentified and untreated and they may then shed disease into the flock.

- Vaccination may not be undertaken for a disease of concern on your farm, and avoidable sickness and production losses may be experienced.

- Treatment for internal and external parasites may not be undertaken on your farm and avoidable conditions and production losses may result.

3.1.7.3 Risk Management Practices

In the table below are some of the protocols you should use to establish the risk management practices in your farm's biosecurity plan for these potentially high-risk activities. The goal is to ensure that specific practices are in place on your farm, supported by descriptive protocols, to address the risks that can relate to these specific activities:

|

Activity |

Suggested Protocols |

|---|---|

|

Lambing |

|

|

Abortion management |

|

|

Milking |

|

|

Disease testing |

|

|

Vaccination |

|

|

Parasite control |

|

3.1.8 Strategy 8 – Limit access by pests, dogs, cats, predators and wildlife

A pest control program is in place and its required procedures are followed. Dogs and cats are vaccinated and spayed and treated for diseases of concern Their access to sheep housing areas and to manure, placentas, deadstock and other potential sources of contaminated material is controlled (e.g. reduce risk of infection with toxoplasma or dog tapeworms). A predator control plan is in place.

3.1.8.1 Description

Pests, dogs, cats and predators may carry diseases or parasites that can directly infect sheep (eg parasitism such as toxoplasmosis from cats and some dog tapeworms). They also have the opportunity to encounter infected material and to transport it to and possibly deposit it on your sheep. Infected material may be feces and other secretions, deadstock, placentas and aborted foetuses, and in some cases material picked up from live sheep or other animals, including blood and tissue. The infected material may be deposited directly on your sheep, but is more likely to be distributed in their environment – in feed and water, in bedding and on surfaces within their pens, sheds, etc. In the case of aggressive contact by predators, direct infection with rabies and other specific pathogens is possible.

3.1.8.2 Risks

- Sheep may be infected by external parasites and/or the intermediate stage of dog tapeworms (e.g. Cysticercus ovis).

- Infected material may be transmitted physically to the sheep environment – on feed, bedding and in waterers – either directly or through the pet's/pest's/predator's digestive system.

- Cats with access to the flock may infect sheep with toxoplasmosis.

- See also Nature of Risk in the table below

3.1.8.3 Risk Management Practices

In the table below is a list of potential pathogens (pests, dogs, cats, predators and wildlife), a description of the nature of the risk they represent, and a list of some of the proactive tactics you should include in your biosecurity plan to reduce the disease-transmission risk represented by their access to your sheep facilities:

|

Agent |

Nature of Risk |

Proactive Risk Management Practices |

|---|---|---|

|

All |

Access by pests, dogs, cats, predators and wildlife; transmission of pathogens by prior contact with placentas, deadstock, etc. |

|

|

Pests (e.g. rodents, flies, other insects) |

Transmission of pathogens by prior contact with other animals, manure, placentas, deadstock, etc.; direct interaction with sheep and contamination of feed, in storage or in feed bunks, and water |

Note: Prevent access by sheep and lambs to pesticides and other control substances |

|

Dogs and cats |

Infection with diseases of concern on the farm (e.g. rabies); transmission of pathogens by prior contact with other animals, manure, placentas, deadstock, etc.; direct interaction with sheep and contamination of feed and water |

|

|

Predators |

Direct attacks on sheep and lambs |

|

|

Wildlife |

Direct or indirect contact |

|

3.1.9 Strategy 9 – Implement health standards for guardian and working animals

Guardian and working animals are vaccinated, dewormed (e.g. tapeworms) and treated for diseases of concern.

3.1.9.1 Description

All guardian and working animals should be vaccinated against rabies and any other diseases of concern. De-worming with a product that is effective against tapeworms is also an important practice to maintain their health and to protect other animals on the farm.

3.1.9.2 Risks

- Guardian animals may encounter wildlife that is infected with rabies and become infected themselves, and may transmit it to your sheep.

- Guardian animals may be attracted to a dead sheep or lamb or to placentas or abortion materials and transmit pathogens to your flock.

- Camelids (llamas, alpacas) share some diseases with sheep, and may infect them during close contact or by being housed in common facilities.

- Guardian dogs may ingest tapeworm larvae or other larvae when scavenging deadstock and these might enable the development and transmission of tapeworms or larvae of different types to your sheep.

3.1.9.3 Risk Management Practices

- Guardian animals should be vaccinated for rabies, and guardian dogs should be treated effectively for tapeworm

- If guardian animals are fed from deadstock, the deadstock should be frozen for a minimum of 14 days or cooked before feeding, to destroy and thereby avoid the transmission of any pathogens, especially C. ovis.

3.2 Principle 2: Record Keeping

Goal – Have records that validate the health status of your flock

3.2.1 Strategy 1 – Maintain and review farm records

Farm records for production, operations animal health and biosecurity are integrated together. Records include goals, analysis of the records to determine current flock status and strategies to reach goals, and are reviewed regularly. Records of health events and diagnostic test results are used both to initiate interventions and change to the flock health program, and are important when selling animals to other producers.

3.2.1.1 Description

Farm records should include:

- Visitor Log

- further described under Principle 4;

- Production records

- a standardized way of recording daily, weekly, monthly or cyclical production that will allow comparison to production goals and between animals: milk production, lamb production, volume/weight/quality of wool produced, etc.;

- Feed records and bedding records

- including source and location (on-farm or purchased);

- Drug records

- keep lot numbers and expiration dates of medications;

- Animal identification

- a standard way of identifying all animals in the flock, consistent with the Canadian Sheep Identification Program (CSIP) standards, that can be linked to an identifier on each animal when observations are made; basic information about their source and genetics, if available, would be included;

- Movement records

- a standard way of recording animal movements on and off-farm, consistent with CSIP;

- Monitoring/surveillance

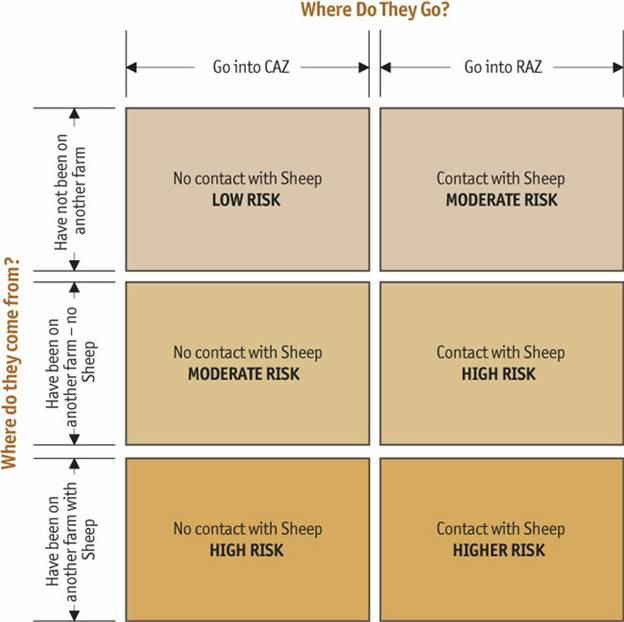

- of disease occurrences and interventions – notes describing observations of clinical signs and the progress of the disease from earliest stages to resolution; this includes disease surveillance at the farm-level carried out by producers to keep track of any health problems that they see and plan to review with their flock veterinarian. Examples include number of cases of pneumonia, number of animals culled for poor body condition, number of cases of diarrhoea in neonatal lambs etc;